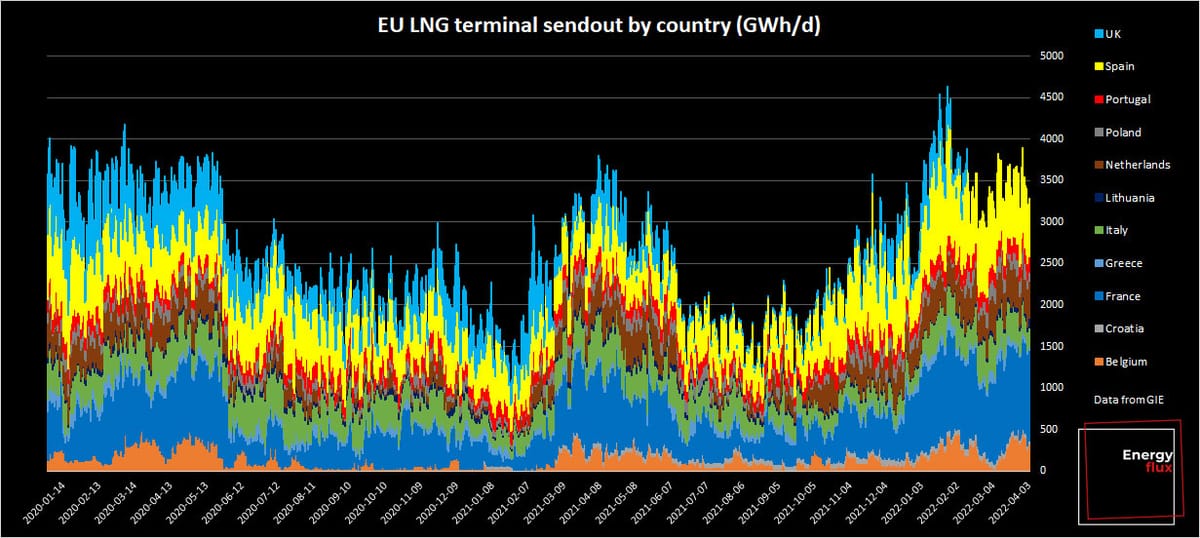

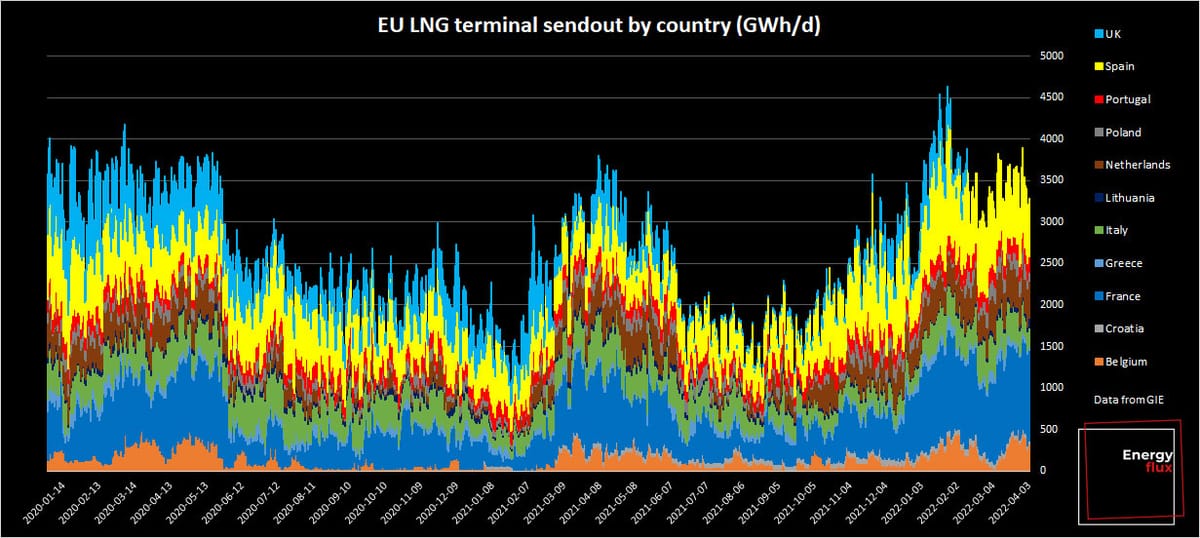

Infrastructure overkill?

Rush to build out EU LNG import capacity seems a bit flawed

Member discussion: Infrastructure overkill?

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

Rush to build out EU LNG import capacity seems a bit flawed

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

Who pays when risk management itself becomes riskier and more expensive?

Gunboat diplomacy, commodity shocks, and the price of escalation

Natural gas markets implode in frenzy of automated selling and cascading long-stop orders

Algo traders take a breath after being taken to the cleaners