Back to Baku

Reporting from Baku Energy Week, and a press trip out to Oil Rocks - one of the weirdest places in the energy world

Azerbaijan occupies a fascinating and complex role on the energy-geopolitics map, wedged between north-south and east-west axes of Eurasian cooperation and conflict. So, I am very excited to be back in Azerbaijan for Baku Energy Week.

I'll be reporting from the conference floor at the Baku Energy Forum, which is packed with dignitaries and high-ranking politicos from across the region.

I'll also be taking a once-in-a-lifetime trip out to Oil Rocks – the world's first offshore oil platform that evolved into a surreal floating city of rusting oil gantries and bridges that sprawl across the Caspian Sea.

The isolated and highly secretive Neft Daşları (Oil Rocks) is now a crumbling homage to Soviet-era decline and environmental mismanagement. This 2016 documentary trailer gives a sense of how inaccessible, unique and frankly weird this place is:

Oil Rocks is a bizarre hulking relic from a long-forgotten era of swashbuckling offshore adventurism. But Azerbaijan is not looking back: Baku has a highly ambitious vision to export clean power across the Black Sea to capitalise on Europe's decarbonisation drive.

To get back in the Baku groove, and to bring readers up to speed with the entangled web of issues facing Azerbaijan's energy aspirations, I am reposting the special report I published after last year's visit.

This 4,000-word feature article, the product of a week-long tour of the country's many and varied energy installations, gives a strategic overview of the energy landscape in the South Caucasus.

Much of the analysis is still current, but bear in mind this post is now a year old; it was written in the run-up to COP29, well before the loss of Ukraine gas transits and the TTF-twisting fake news cycle that led many to believe Azerbaijan might play a role in facilitating continued Russian pipeline exports to Europe.

That story is still infolding, which is why I'm here: to find out what the next chapter could mean for European gas and power markets. Azerbaijan's hybrid fossil and renewable export ambitions could move the needle on physical energy balances, but only if Baku plays its cards right.

The main protagonist in the Azerbaijan gas story is (of course) regional geopolitics and shifting bilateral relations. I'll be reconnecting with folks at SOCAR, the energy ministry, and other well-connected industry players to bring you the full picture.

Join me as I explore Baku's dilapidated infrastructure and moonshot clean export plans to decipher whether stranded Caspian resources still have a future in the fraught Eurasian energy puzzle.

– Seb

P.S. The reposted deep dive looks even better now I'm using Ghost's flashy multimedia content editor. Check it out below, even if you read it last time (or better still, read it in your browser).

I've lifted the paywall on this 2024 Deep Dive, but paid subscribers read it first a year ago.

Sign up to Energy Flux for timely, independent, on-the-ground reporting from Baku Energy Week & Oil Rocks!

REPOST: War, peace and energy in the land of fire

DISPATCH FROM BAKU: Can a ‘green corridor’ of energy trade heal deep wounds in the South Caucasus?

BAKU, 22 APRIL 2024: They say that peace and prosperity go hand in hand. But Azerbaijan, the small South Caucasus country transformed by Caspian oil riches, proves you can have one without the other.

An influx of petrodollars since the early 2000s propelled Azerbaijan from post-Soviet backwater into a regional economic and military powerhouse. Azerbaijan’s armed forces decimated neighbouring Armenia in a series of stunning and decisive offensives between 2020 and 2023 that reasserted Baku’s control over the Nagorno-Karabakh region and occupied territories.

The two countries are technically still at war, although the Azeri people want to believe otherwise. Azerbaijan’s battlefield successes “settled” the issue, residents of Baku will impress upon you. Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s autocratic president, says the warring nations are “closer to peace than ever before” — a wishful line parroted by charming Azeri politicians in Azerbaijan’s chic and ostentatious capital.

Oil wealth oozes from every corner of the city. Glass-fronted skyscrapers soar over an immaculate Caspian seaside boulevard dotted with enticing Persian-Anatolian eateries. The picturesque cobbled streets of the painstakingly restored old town send a very clear message: energy trade brings wealth, power and regional dominance.

For Armenia, the situation is dire. Aside from so much else, the decades-long conflict cost Armenia the opportunity to become a transit country for Caspian hydrocarbons. Lucrative transit fees instead went to Georgia and Turkey, leaving Armenia economically isolated. Politically too the country is adrift after being abandoned by long-time ally Russia.

Now, Azerbaijan’s upcoming presidency of COP29 is throwing a spotlight on the South Caucasus and its untapped renewables potential. Ministers in Baku want to promote the idea of a ‘green peace corridor’ — an electricity interconnector that unites feuding neighbours around a shared undertaking: to export pan-Caucasian wind and solar power to premium markets in Europe.

European leaders are keen on the idea. Green infrastructure that forges an enduring peace deal while diversifying European energy sources and decarbonising coal-heavy Balkan power grids is a win-win-win. But there’s a catch: cross-border cooperation and investment won’t happen without a lasting diplomatic accord between Baku and the Armenian capital of Yerevan.

This is a region still processing the harrowing fallout from decades of failed diplomacy and armed conflict. Armenia last week alleged Azerbaijan undertook “ethnic cleansing” and destroyed Armenian cultural heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh. Baku says Armenia’s 30-year occupation of territories on the Iranian border left the region contaminated with mines and toxic pollutants. Both sides accused each other of violating the terms of a ceasefire agreement during a cross-border skirmish in early April, prompting G7 leaders to weigh in.

Against this backdrop, what chance is there that the distant promise of green export riches will focus minds at heated peace talks?

Zoom out, and the picture becomes more nuanced. Azerbaijan might have won the war, but it still needs to cooperate with Armenia to win the peace — and there are some encouraging signs on that front. In parallel, the COP29 host is embracing renewables to diversify its fossil fuel-reliant economy and free up natural gas for export. An initial 2 GW of wind and solar is due online by 2027, but expansion beyond that requires access to premium export markets — and Armenia, to an extent, stands between them.

Looking wider still, Azerbaijan and Armenia sit at the gateway between east and west. An enduring peace settlement could open a vital new trade corridor between energy-poor Europe and energy-rich landlocked Central Asia. With war raging in Ukraine, nations on both sides of the gateway are keen to unlock the opportunity — putting the issue of Azerbaijan-Armenia relations at the heart of geostrategic Eurasian energy and climate considerations.

When it comes to energy geopolitics, the South Caucasus is one of the world’s most complex regions to unpick. This (rather long) special dispatch from Baku analyses the oil, gas and renewables outlook for Azerbaijan, and the sensitivities of developing energy flows across borders still bristling with tension.

The region tends to fly under the radar of energy observers, but high-stakes peace talks could determine the energy future of the South Caucasus and, by extension, Europe.

💥 Article stats: 4,200 words, 20-min reading time, 12 charts, graphics, videos, maps & photos

Researching this article involved numerous flights over two weeks of travel, many hours of interviews, reams of notes and a fair bit of data wrangling. None of this would be possible without the support of paid subscribers.

Third time lucky?

Hopes of building a ‘peace pipeline’ to soothe Armenia-Azerbaijan relations have been dashed not once but twice.

There was talk in the 1990s of including Armenia in what is now the wending Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline that pumps Caspian oil from Azerbaijan up through Georgia and down to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. The same was said about the South Caucasus Pipeline, which forms the easterly section of the Southern Gas Corridor carrying natural gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz offshore gas field to southern Italy.

For the sake of expediency, on both occasions the decision made for these pipes to circumvent Armenia and thus the conflict itself.

Azerbaijan’s deputy energy minister Elnur Soltanov said at a media briefing in Baku last week:

“We missed that boat [on a peace pipeline], but maybe this is the time for a green peace corridor."

Soltanov, who has taken on a second job as the CEO of Azerbaijan’s COP29 presidency, said Baku wants to deliver a “peace dividend” following Azerbaijan’s military conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh and recapture of territory previously occupied by Armenia.

Peace powerline pain-points

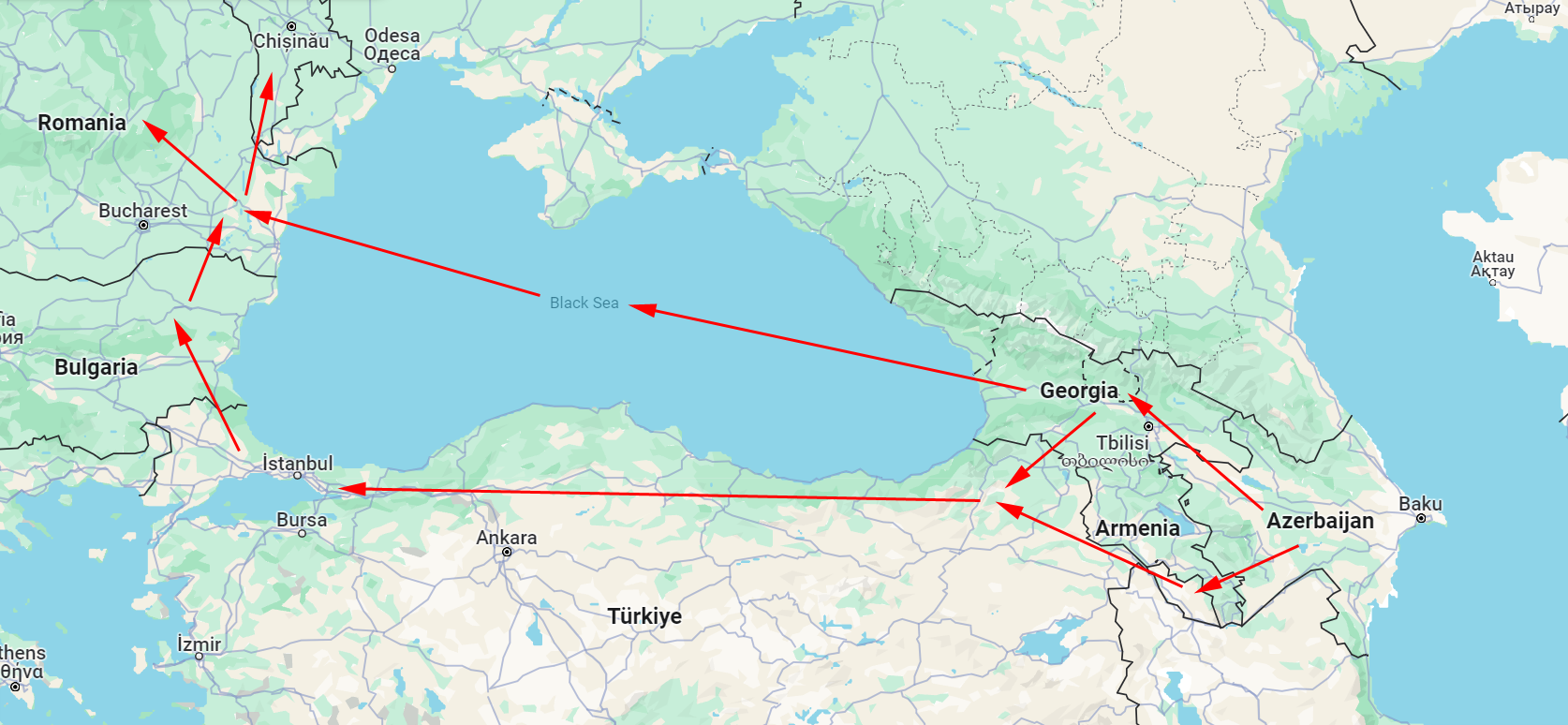

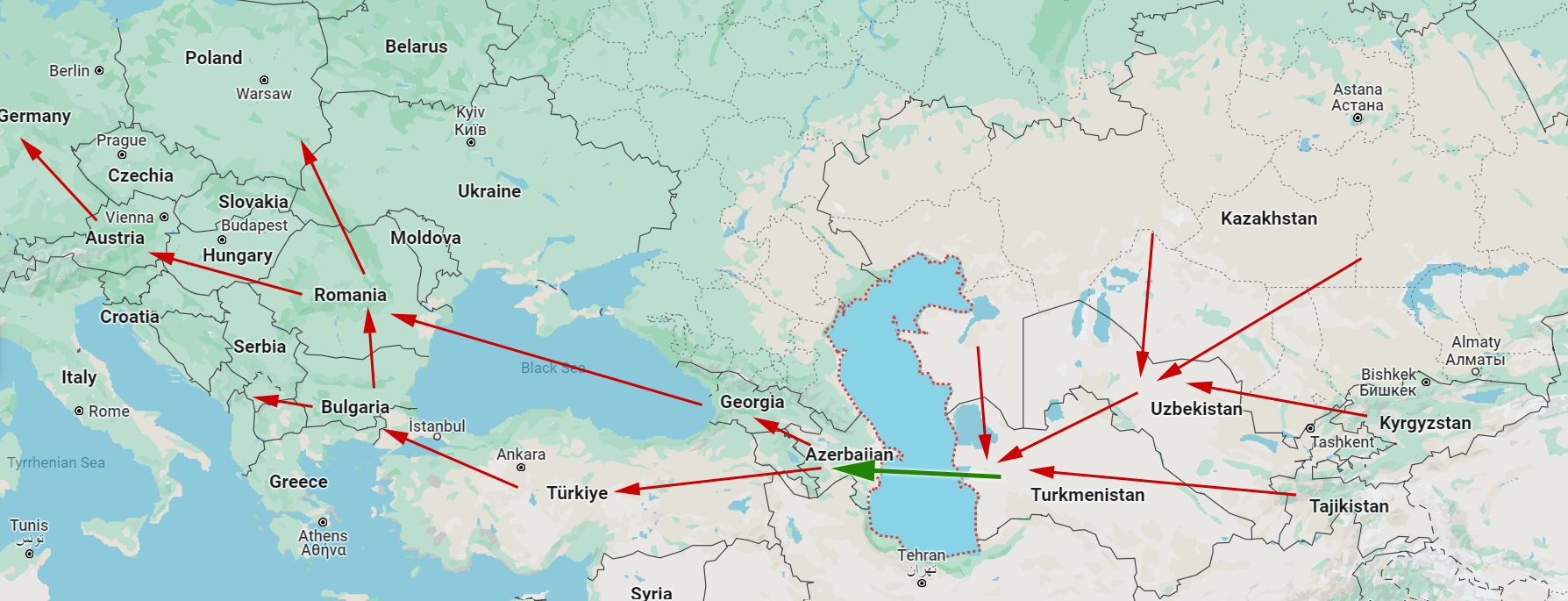

There is much talk in Baku about COP29 injecting momentum into a ‘green corridor’ of sustainable energy trade and investment. The idea is to position Azerbaijan as a key exporter of zero-carbon electricity to Europe. Two main interconnector routes are under consideration: a subsea power line under the Black Sea from Georgia to Romania, and a terrestrial transmission line via Armenia, Turkey and the Balkans.

Neither of these ‘green corridor’ concepts is straightforward. The Black Sea route has been contemplated since 2014 as a simple 1 GW high voltage direct current (HVDC) EU interconnector for Georgia. Azerbaijan joined the project a couple of years ago as a means of evacuating wind and solar power, jacking up the cable’s mooted capacity to 3 GW or 4 GW, according to sources in Baku.

While interest has grown over time, so have the challenges it faces. Laying a 1,100 km high-voltage submarine cable at water depths of more than 2,000 metres is a vastly ambitious technical undertaking that could cost upwards of €2.3 billion. Add to that the logistical and insurance implications of cable-laying near an active warzone, and the project would seem unviable until there’s an end to hostilities in Ukraine and warships no longer patrol the Black Sea.

But sooner or later that day will come, and leaders from Romania, Hungary, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and the European Union are making high-level preparations in earnest. ENTSO-E, the European Network of Transmission System Operators, included the Black Sea interconnector in its latest ten-year network development plan. The project’s official status is ‘under consideration’ with a tentative (read: optimistic) in-service date of December 2029.

Enclaves and exclaves

The terrestrial option might seem quicker and easier. But again, even the relatively simple first step — a power line from Azerbaijan to Turkey via Armenia — is mired in difficulty.

Azerbaijan is split into two distinct territories: the ‘mainland’ to the east, and the landlocked exclave of Nakhchivan to the west. Armenia sits between the two. Nakhchivan’s energy system used to be connected to mainland Azerbaijan by pipes and power lines but these were largely destroyed during the war, Soltanov said.

“We need to connect Nakhchivan to the mainland. It should and could go through Armenia and from there through Turkey and all the way to Europe also, and in fact it’s part of the quadrilateral agreement that we have [with Armenia, France and the European Council]. We believe that these corridors could also have some sort of peace dividend, this is one of the ideas we are entertaining." – Deputy energy minister Elnur Soltanov

Tensions in Zangazur

It is a noble objective. But head west from Baku towards the Armenian border, and the idea starts to sound fanciful.

Azerbaijan is rebuilding old Soviet-era transport links with Nakhchivan via its southern ‘liberated territories’ that were recaptured following 30 years of Armenian occupation. The project envisages a road and railway crossing Armenia’s southern territory — the Zangazur (AKA Meghri) corridor. Azerbaijan demands it should control the corridor and border checkpoints, which Armenia rejects.

Armenia tried to “block” the project, according to Nijat Karimov, an official in East Zangazur who advises the region’s representative to President Aliyev. “It is another mistake they made because there are always alternative ways,” Karimov said during a tour of the new Agali ‘smart’ village in Zangazur last week.

Armenian authorities will hopefully have a change of heart “very soon”, he added. But if they don’t, the railway would instead pass over Azerbaijan’s southern border and enter Nakhchivan via Iran, bypassing Armenia altogether. Sound familiar?

It gets worse. Control of the Zangazur corridor is a highly sensitive matter and there are fears that it could be the next flashpoint in the crisis. Russia, which participates in a tripartite dialogue over Zangazur, has its own interests in developing a north-south trade corridor through Armenia to Iran. Without a hint of irony, Moscow last week called for all sides to exercise “restraint”.

A military solution to the Zangazur question would kill any hopes of Azerbaijan building an overground interconnector to Europe via Armenia. The idea of rerouting via Iran might work for a regional railway, but European leaders and multilateral lenders would be hard-pressed to support a transmission project that benefits Iran and further isolates Armenia.

Crimped by the grid

This is a problem for Azerbaijan. The government is desperate to showcase its green credentials and needs a compelling renewables growth story to tell when the world’s media descends on Baku for COP29 later this year. Solving the Zangazur puzzle would give credence to Azerbaijan’s future renewables aspirations.

The country is making progress within the confines of existing infrastructure. Installed renewables capacity is on track to rise from today’s 1.6 GW to 3.6 GW (30% of total capacity) before 2030. This will be delivered by an additional 2 GW across eight wind and solar projects that are due online by 2027, all of which can be integrated without significant grid upgrades.

Further ahead, however, officials are planning an enormous 10 GW pipeline of wind and solar projects that would overwhelm the gas-rich country’s 9 GW electricity system.

Going beyond 30% renewables “is the threshold from which we will need additional support or strengthening of the grid,” said Kamran Huseynov, deputy director of the state-run Azerbaijan Renewable Energy Agency (AREA).

Speaking during a tour of Masdar’s 230 MW Garadagh solar PV plant, he said the export connection is vital to exceeding 30% RE.

Renewables force reform

Renewables plants such Garadagh operate as independent power producers (IPPs) whose output offsets thermal generation from Azer Energy, the state monopoly with sole responsibility for generation, security of supply and grid stability.

Officials are keen to talk about how much gas is saved from Azerbaijan’s renewables push, but the regulatory framework overseeing this transformation is not fit for purpose.

Electricity market reform and monopoly unbundling has been on the cards since 2016. The process hasn’t officially begun, but IPPs are forcing the issue.

“So by introducing the new IPPs we are also kicking off with an electricity market,” Huseynov added.

In parallel, AREA is looking at battery storage and production of green hydrogen to integrate more wind and solar. This adds extra urgency to the reform process.

“Who would be in charge of the battery storage? Who is covering the cost? You either put it as the responsibility of the IPP or the grid operator. Will it affect the [renewable] production tariff or will you have an additional battery storage tariff for ancillary [services] payment? These are all questions we are working on to see how we can implement projects beyond 2027.” – Kamran Huseynov, Azerbaijan Renewable Energy Agency

Caspian wind — electrons or molecules?

Market liberalisation and grid constraints must be fixed before Azerbaijan can exploit its Caspian offshore wind resource, which requires gigawatt-scale developments.

Azerbaijan is working with Masdar to identify zones for an initial 2 GW of offshore wind that would come online post-2027, potentially rising to 6 GW later. Securing end-user commitment will be key to getting projects off the drawing board.

The only destination market able to provide a demand anchor of this size is Europe, but transmission is a challenge. Azerbaijan is also looking at hydrogen as an alternative energy vector for enabling Caspian offshore wind. Similar obstacles present themselves here too.

The EU, again, is the only viable market for Azerbaijani hydrogen exports. There is no market pull from domestic industry for green H2, and regional neighbours don’t need it either.

“Nobody in Central Asia is going to pay a premium for green hydrogen,” said Teymur Guliyev, deputy VP energy transition at SOCAR. “If they want to, they can do it on their own. Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, they have massive natural resources for green energy generation.”

The Southern Gas Corridor could be upgraded to carry hydrogen, but Azerbaijan can’t do it alone. This would only work “if they can get some consortium going, similar to what we saw when they built the SGC, maybe seven countries and a number of companies,” Guliyev said.

It doesn’t make sense to export both commodities because the infrastructure serves the same purpose. “Either way, you’ve got to get the energy from Azerbaijan to the EU,” he said.

“The question is, do you … build new hydrogen pipelines, or do you use the Black Sea submarine cable to Europe and then you just export the green electrons and let them produce the hydrogen on their side? That is an open question,” he said.

So, Caspian offshore wind development hinges on Azerbaijan forging international partnerships to secure long-term offtake deals and a viable westerly route for energy export infrastructure. Is it maybe all too difficult? And if so, is there an easier way?

All roads lead back to gas

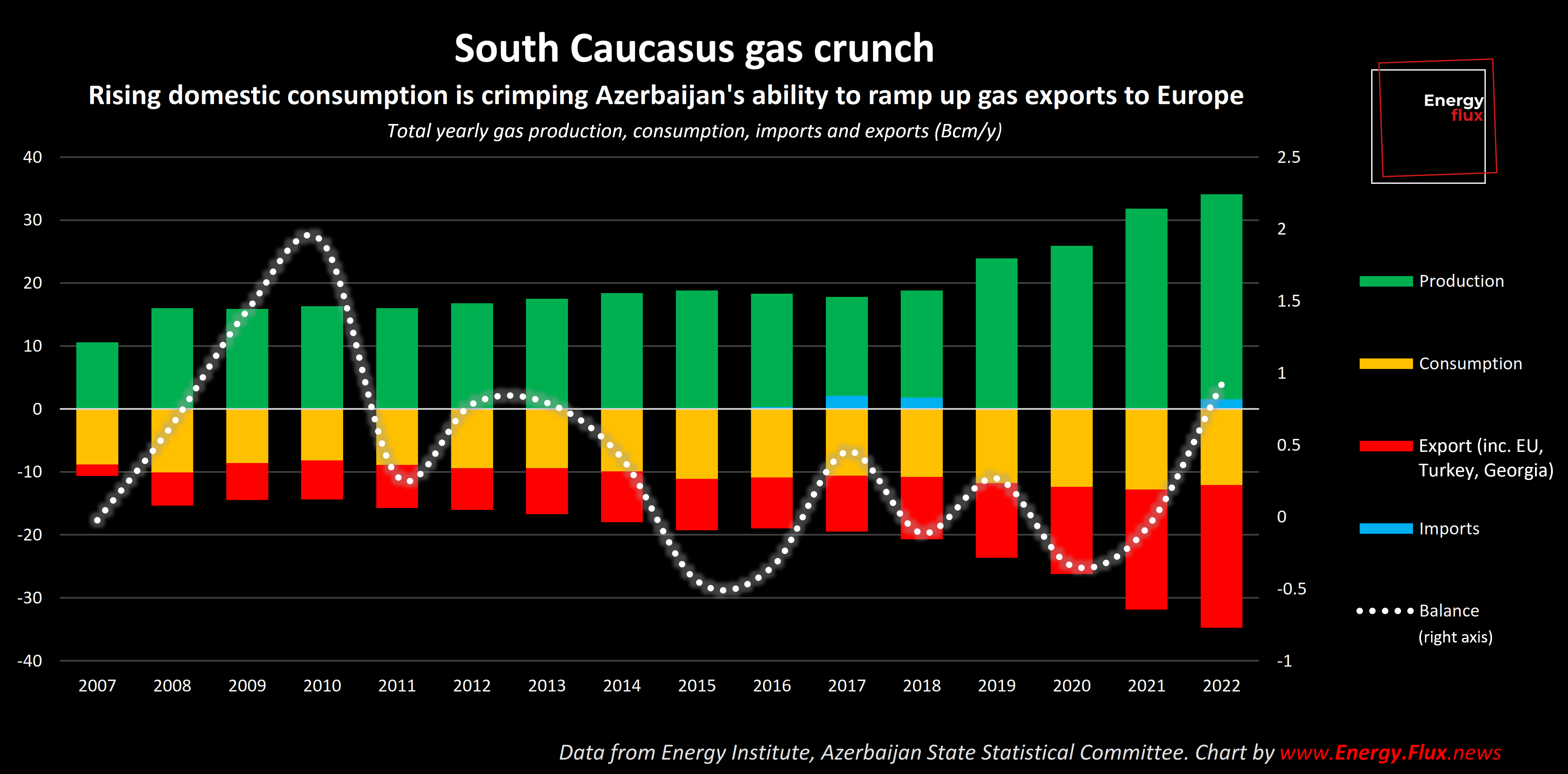

Today, piping natural gas to Europe is Azerbaijan’s simplest energy export option. Upstream supply, transmission infrastructure and demand commitments are all in place. But domestic demand is rising almost as quickly as production is growing, gobbling up the slack.

Azerbaijan exported 12.9 billion cubic metres (Bcm) of gas to Europe along the SGC last year (plus a similar amount to Turkey). It expects that to rise to 14 Bcm by 2026 and is targeting 20 Bcm per year from 2027, although there are doubts about SOCAR’s ability ramp up production in time.

Wind and solar fix this by displacing domestic gas-fired generation and freeing up methane molecules for export. In fact, this is the primary motivation for Azerbaijan’s renewables pivot.

“Our internal gas consumption is around eight billion cubic metres. Now with these renewable projects coming into effect we can use renewable energy for internal use and free up around 8 Bcm of gas,” said Mustafa Garbanli, head of environmental disclosures and green affairs department at SOCAR.

Greening the gas chain

Renewables also help to reduce the upstream emissions footprint of Azerbaijan’s gas production, alongside plugging methane leaks and eradicating routine flaring. With the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) coming into force from 2026, cleaning up the gas value chain is becoming a pressing issue for SOCAR.

“If we don’t do that, there will be penalties so our gas will not be competitive [and] we will not survive,” Garbanli said. Environmental considerations are no longer “just ethical and moral, now it is both financial, ethical and moral. That’s why there is no way out.”

SOCAR also needs to expand transmission capacity on the SGC to hit 20 Bcm. This means upgrading compressors along the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), the westerly segment of the SGC that runs from Turkey through Greece to Italy. Again, SOCAR, which owns 20% of TAP, can’t do this alone and needs European partners to commit to ship extra volumes to make the investment worthwhile.

In parallel, plans are afoot to boost exports via the ‘Solidarity Ring’, a project to reinforce existing pipelines between Turkey and the Balkans and beyond. The EU-backed Solidarity Ring would enable gas to be diverted from the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) segment of the SGC northwards as far as Ukraine and Hungary. Again this requires consortium buy-in, but if it comes together it might render the TAP expansion redundant.

Caspian oil’s last hurrah

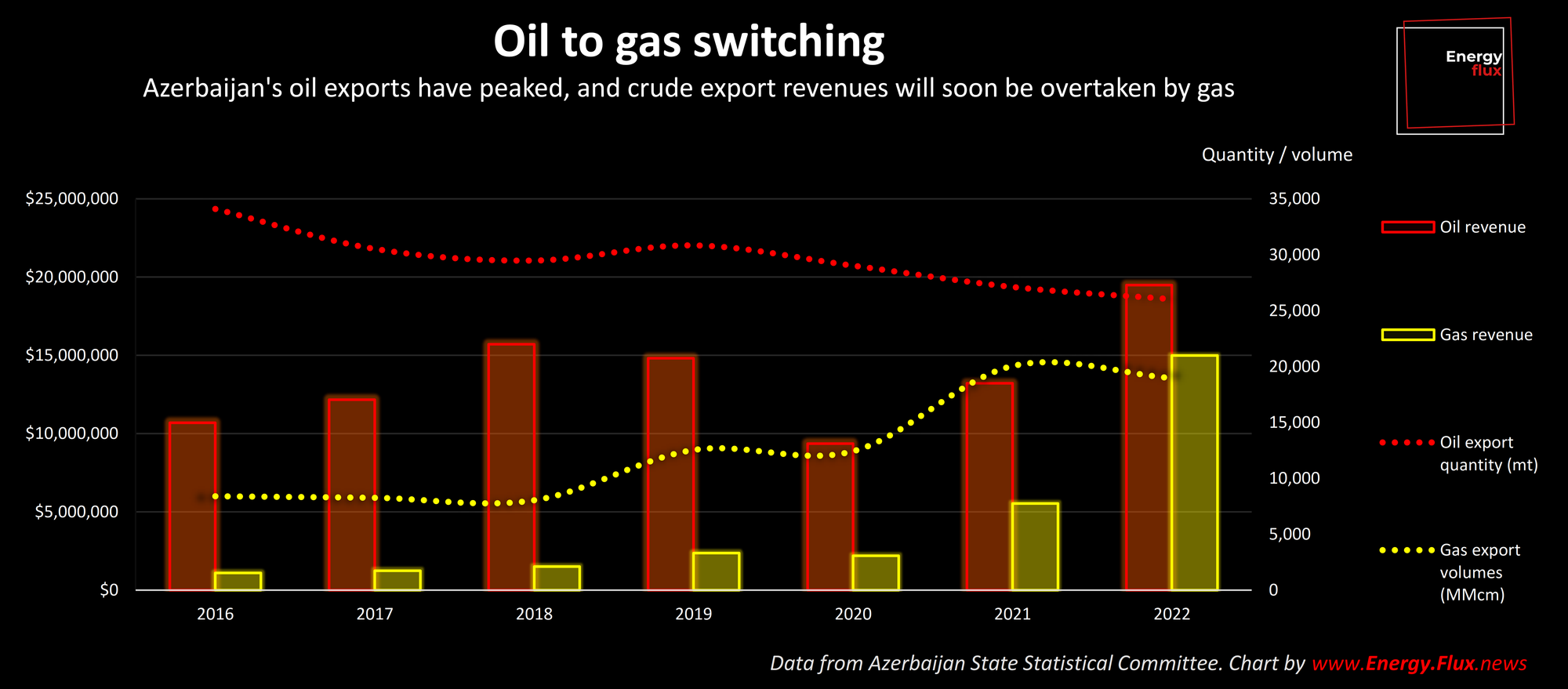

The ramp-up in European gas exports has given Azerbaijan a huge cash injection. The country earned $15 billion from gas exports in the energy crisis year of 2022, up from $5.5 billion the previous year and $2.2 billion in 2020.

The gas windfall has come in handy. Baku’s oil revenues are highly unpredictable and reflect the volatility of global markets, lurching from $15 billion in 2019 to $9 billion in the pandemic year of 2020 before soaring to $19 billion in 2022, following Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine.

The variability masks the fact that Azerbaijan’s oil export volumes are in terminal decline. Exports peaked at 30 million tonnes (mt) in 2019 and have fallen every year since, clocking in at 26 mt in 2022. Ministers expect this to fall by another 8.8% by 2027.

To offset the decline, Azerbaijan is turning into a transit country. Last year, Kazakhstan began shipping oil from the vast Tengiz field to Azerbaijan’s Sangachal terminal on the Caspian. From there it is pumped into the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and towards global markets.

Azerbaijan also wants to re-open a pipeline to Georgia’s Supsa terminal on the Black sea to open another non-Russian export route for Kazakh oil. This has the added benefit of avoiding the need to mix heavy Kazakh crude with lighter Azeri oil grades in the BTC pipeline.

Resurrecting the old Silk Road

Azerbaijan’s pivot from oil exporter to transit country for Kazakh crude might seem like a hopeless backwards step. But, perhaps ironically, it exemplifies the forward vision needed to position the country as a crucial Eurasian trade link.

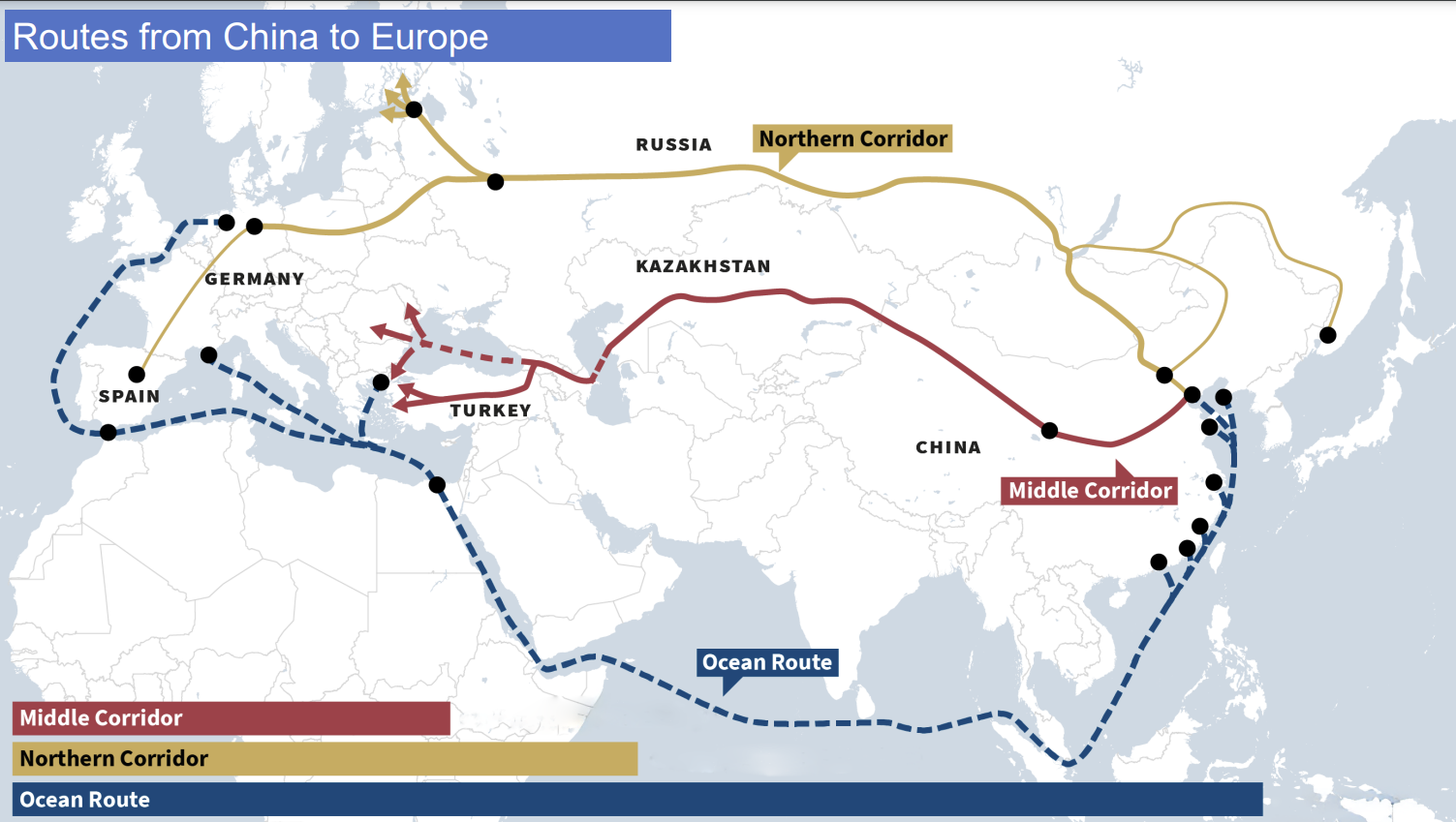

Before February 2022, 86% of terrestrial trade between Europe and China transited through Russia along the so-called Northern Route. Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine and ensuing Western sanctions made this less attractive, presenting an opportunity to challenge Moscow’s transit monopoly. Meanwhile, Houthi attacks on Red Sea commercial vessels have complicated seaborne trade, pushing exporters to seek safer alternative routes.

Thanks to a confluence of global crises, the old Silk Road is being reincarnated as the Middle Corridor — a multimodal transport system consisting of existing rail and port infrastructure.

The Middle Corridor offers benefits in its own right. Shipping distances are shorter, allowing for expedited transit times, and it avoids Russia altogether. Amazingly, Azerbaijan’s energy transition — such that it is — is already stimulating trade in green energy components along this passage.

Blazing a trail to Baku

ACWA Power, the Saudi state-backed renewables developer, intends to use the Middle Corridor to ship bulky 6.5 MW Chinese wind turbine components to a 240 MW onshore wind farm it is developing in Azerbaijan’s Absheron and Khizi districts.

ACWA originally intended to ship components by sea from factories on China’s east coast via Turkey and Georgia, said Ashley Rowlands, ACWA Power project director. ACWA then looked at using river barges through Russia, before settling on the 7,000 km overland route via Kazakhstan, using roads for oversized components and railways and ships for smaller containerised items.

The 111 blades and tower sections for the project’s 37 Envision turbines will ride through Kazakhstan before being loaded onto vessels and shipped across the Caspian Sea to the Port of Baku — which is gearing up for a major expansion in anticipation of a surge in terrestrial east-west trade flows, including a future buildout of Caspian offshore wind farms.

Trans-Caspian connection

There’s a degree of overlap between the ‘green peace corridor’ for energy exports and the Middle Corridor for commerce. ACWA Power’s use of the Middle Corridor to deliver equipment to build a wind farm that could, eventually, contribute to Azerbaijani electricity exports to Europe is emblematic of the concept.

“Azerbaijan is looking at the green corridor from [the perspective of] Azerbaijan, but it’s obviously a feeder also for all the other Central Asian countries to feed into Europe through that corridor,” said Rowlands.

To enable those energy flows, long-lost plans for a Trans-Caspian pipeline are being resurrected also — but with a green twist.

The subsea gas pipeline project from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan has been dead in the water for some time. But phenomenal progress developing wind and solar resources in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan is injecting fresh momentum into a Trans-Caspian power line — or even a Caspian hydrogen pipeline — to deliver those Central Asian green energy sources to Europe via Azerbaijan.

Deputy minister Soltanov said he views a Trans-Caspian power line as the most likely contender, while ACWA Power CEO Selim Güven said a hydrogen pipeline could deliver greater value. The decision cannot be taken in isolation and must be coordinated with onward connections to Europe.

Neither will be easy. Just like the Black Sea subsea cable or Trans-Anatolian power line, a Trans-Caspian link requires cooperation at the highest levels and “a vision and political will”, said ACWA’s CEO Güven. Each project is a mammoth undertaking in its own right. Linking them together in a timely fashion is even more ambitious.

Time for another miracle

It is tempting to be pessimistic, but the combined force of a market ‘pull’ from Europe and a market ‘push’ from Central Asia should not be underestimated. If they can overcome their differences, Armenia and Azerbaijan are perfectly positioned to reap huge economic benefits, both in terms of energy flows and commerce, through their respective territories.

Azerbaijan has been the driving force behind not one but two trans-regional energy infrastructure projects in the form of the BTC and TANAP/SGC pipelines. Sceptics poured scorn on both projects at the time, yet Baku’s wealth stands testament to its ability to forge partnerships that make impossible Caucasian energy infrastructure projects happen. The city’s prominence as the next COP venue is thanks in part to this achievement.

Azerbaijan is highly motivated to pull off a third Caucasian energy infrastructure marvel, and the UN climate conference in November is adding impetus to this endeavour. With Baku about to come under intense scrutiny, Azerbaijan stands to benefit from capitalising on this unique moment to push ahead with the ‘peace corridor’ concept. In so doing, it could mark the start of a new era of normalised neighbourly relations that delivers the ‘peace dividend’ that the region so desperately needs.

“Momentum is building” said ACWA’s CEO Güven. “Azerbaijan is a gateway which we would like to grow further. This is only the beginning of the story.”

Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 22 April 2024

If you enjoyed that (very) deep dive, sign up to Energy Flux for for more honest & fiercely independent energy journalism

Member discussion: Back to Baku

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.