❄️Frozen out of a warming Arctic🔥

DEEP DIVE: Is Russia losing its grip on Arctic energy resources?

Member discussion: ❄️Frozen out of a warming Arctic🔥

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

DEEP DIVE: Is Russia losing its grip on Arctic energy resources?

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

Self-reinforcing volatility loop sustains sudden winter gas price rally, but for how long?

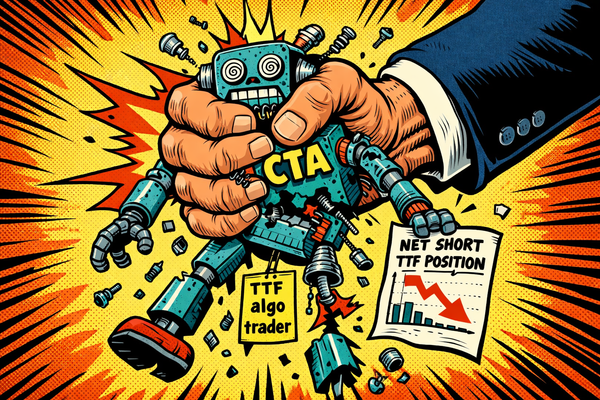

Hedge funds punish complacency in EU gas market. This is a sign of the times.

As the world fixates on oil, Venezuela burns $1.4bn of gas — while sitting on an untouched methane empire that could redraw regional power

2026 OUTLOOK: The Old Continent’s LNG habit could soon be funding two illegal military interventions on its immediate peripheries