Energy markets are so damn fickle

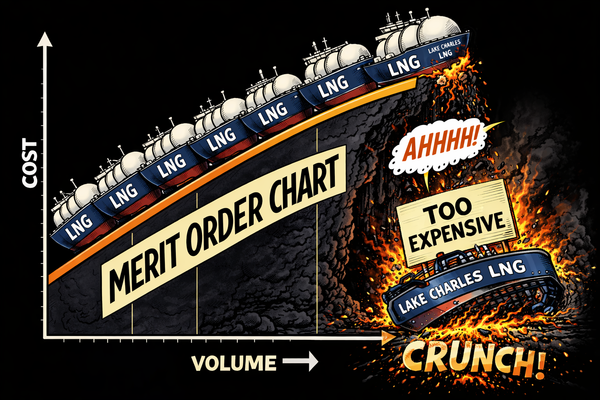

And none more so than natural gas

Member discussion: Energy markets are so damn fickle

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

And none more so than natural gas

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

2026 OUTLOOK: The Old Continent’s LNG habit could soon be funding two illegal military interventions on its immediate peripheries

Chaos looms after audacious decapitation of Maduro regime

How natural gas prices dictate the pace of energy transition

PLUS: Tracking the glut, cheap gas and the energy transition, 2025 in review, Chart Deck + TTF Risk Model update