Energy transition = volatility

Oil and gas investment is simultaneously way too high and dangerously low

Member discussion: Energy transition = volatility

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

Oil and gas investment is simultaneously way too high and dangerously low

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

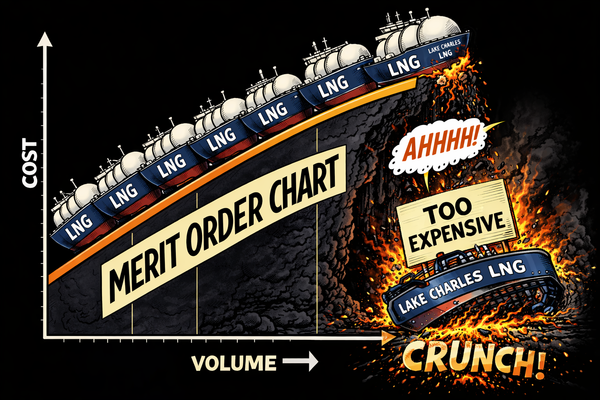

How natural gas prices dictate the pace of energy transition

PLUS: Tracking the glut, cheap gas and the energy transition, 2025 in review, Chart Deck + TTF Risk Model update

New LNG physical balance index monitors glut conditions in real-time | Chart Deck — 19 Dec 2025

Spread compression intensifies, but TTF is primed to snap back | Chart Deck — 12 Dec 2025