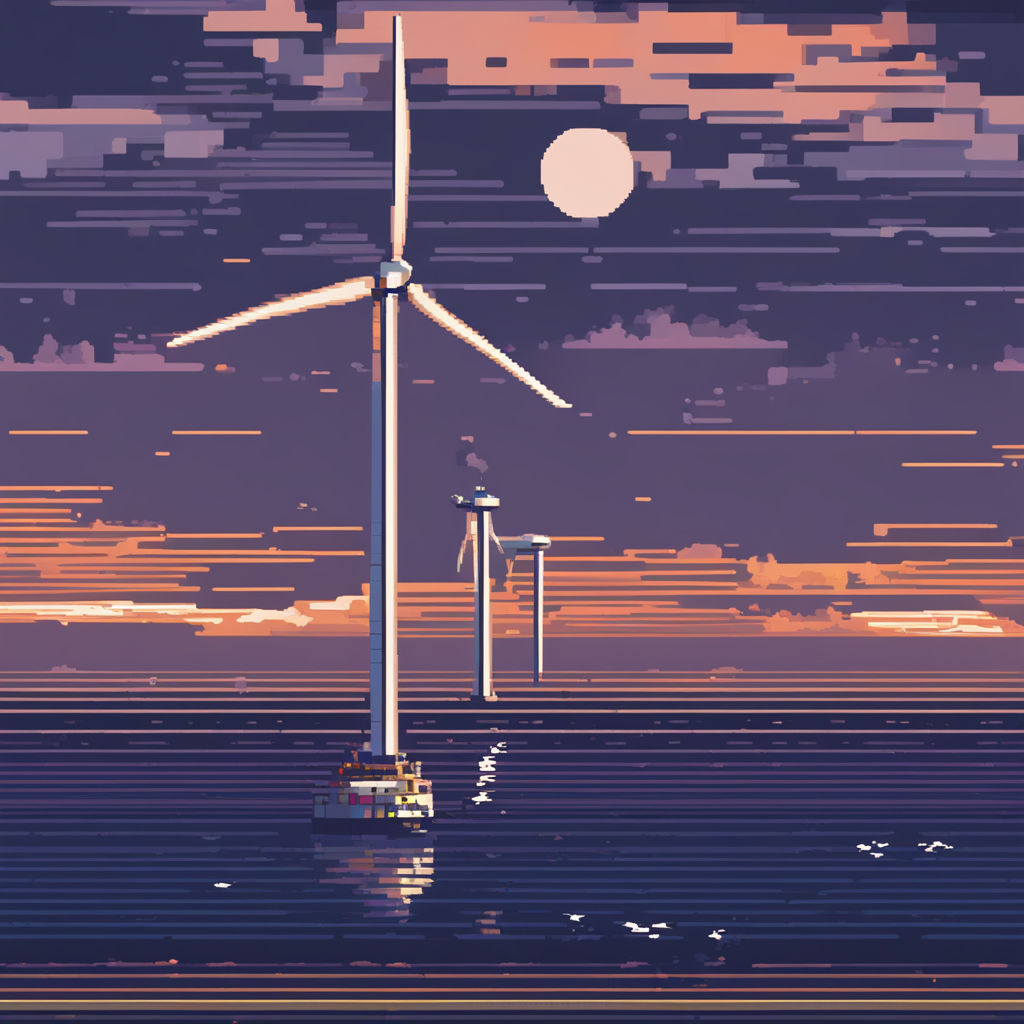

Less offshore wind = more gas, more £££

The UK’s looming offshore wind shortfall could cost billions in extra gas consumption

Member discussion: Less offshore wind = more gas, more £££

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.