Putting the Covid oil crash in context

2020 marked a mere blip on humanity’s meteoric rise in energy demand

Member discussion: Putting the Covid oil crash in context

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

2020 marked a mere blip on humanity’s meteoric rise in energy demand

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.

PLUS: Tracking the glut, cheap gas and the energy transition, 2025 in review, Chart Deck + TTF Risk Model update

New LNG physical balance index monitors glut conditions in real-time | Chart Deck — 19 Dec 2025

Spread compression intensifies, but TTF is primed to snap back | Chart Deck — 12 Dec 2025

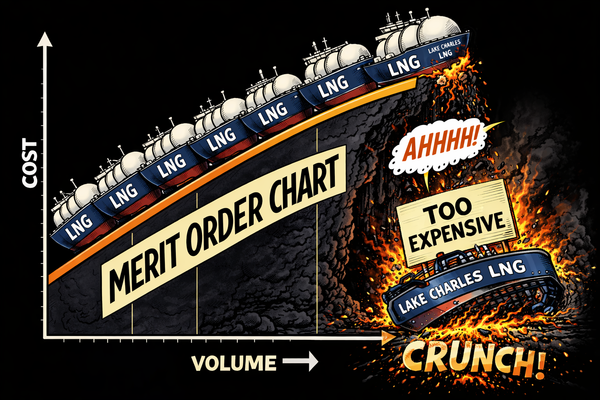

Negative US LNG profits & record-low Henry Hub-TTF correlation signal extreme market dislocation — and looming rebalancing