*REPOST* Lost in transition: Big Oil searches for purpose as peak demand looms

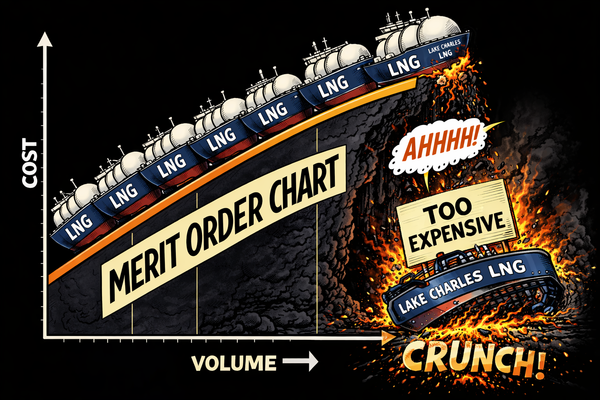

BP’s decision to slash its crude production this decade is brave. But its assumption that pivoting to low carbon will be profitable is heroic

Member discussion: *REPOST* Lost in transition: Big Oil searches for purpose as peak demand looms

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.