Woodside goes it alone on Scarborough LNG

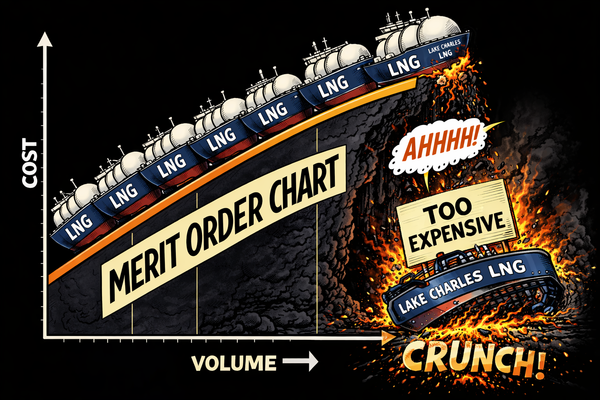

Luring investment into greenfield gas projects is tough, even in a gas-starved world

Member discussion: Woodside goes it alone on Scarborough LNG

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.