UK-Norway gas trade: Time for a New Deal?

If we want to avoid populist parties weaponising energy prices we need to think differently, starting with trade relationships between the UK and Norway.

Article summary (click to expand)

- Co-dependency: The UK relies on Norway for almost half its gas, bought at market rates that hand Norway huge rents and inflate UK bills.

- Misplaced focus: London and Oslo obsess over long-term energy transition tech while ignoring the immediate affordability crisis driven by gas dependence.

- The New Deal: Cost-linked long-term gas sales contracts plus UK-backed storage and infrastructure investment would swap excess rents for political & economic stability.

- Leverage moment: The LNG glut will shrink Equinor’s revenues, giving the UK a rare chance to negotiate new long-term contracts at favourable prices.

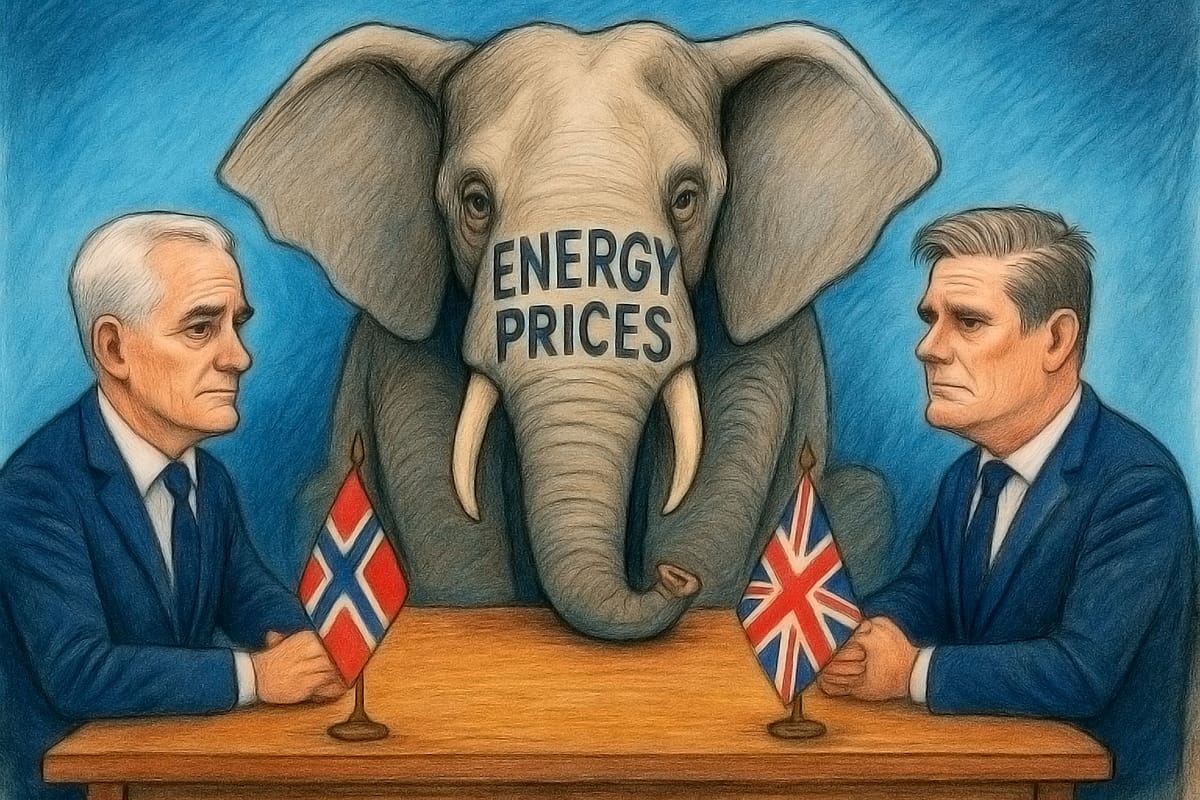

What do Norwegian and British Prime Ministers talk about when they get together? Both are left-leaning governments, both are fending off attacks from the far right. Both are outside the EU and both benefit from the bountiful resources provided by the North Sea, the most valuable of which is — or in the UK’s case, was — oil and natural gas.

The UK’s early discovery of gas coupled with a big economy and large population meant by the 2010s domestic production had already peaked, and was falling much more rapidly than demand. No amount of wishing them away will change these facts.

Norway’s circumstances are different. It is now the UK’s most stable and significant pipeline gas supplier, providing 31 billion cubic metres (Bcm) of gas in 2024 — almost half of our national consumption. And it’s a reliable supplier with high environmental standards and some of the lowest upstream costs in the world (around $2/MMBtu). It also operates a largely nationalised gas energy system for production and distribution.

However, and this is politically very important, this gas is sold at market rates, not production costs, which inflates prices in the UK and generates substantial rents. Equinor’s gas lifting costs are estimated at around $2/MMBtu for large North Sea fields such as Troll, compared to an average realised sales price of $13.5/MMBtu in 2024.

As a result, Equinor’s 2024 pre-tax margin was approximately 25.9% (£22 billion), which, while lower than its 2022 peak of >40%, is still incredibly strong. The Norwegian state owns a 67% stake in Equinor and in addition the government takes 78% in taxes, representing a huge rent from the natural resources they govern (£16 billion in 2024).

There is clearly an energy based interdependence between the UK and Norway: they have the resource, and we have the large local market. Norway produces 33 times more gas than it needs domestically, and the UK provides a reliable and major market (almost 20 times Norway’s internal domestic consumption). This interdependence has seen vast sums accrue to the Norwegian Treasury, at a time when affordability of energy has become a high profile political weapon.

Gas should therefore be a topic of constant conversation between the two countries. However, recent high-level meetings between the UK and Norwegian governments appear to have been dominated by other issues such as defence. And on energy, the focus has been on longer term issues such as renewables, or on cost-adding (and inherently inefficient) initiatives such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen. There has been no dedicated focus on gas strategies or affordability, beyond a passing reference to ‘efficient markets’.

This needs to change.

The UK’s gas dilemma (click to expand)

How self-sufficient is the UK in gas and how does this benefit UK citizens? Since the peak in 2000, UK gas production has fallen by over 70%. At best, we now provide only half of our gas needs, a share that declines year-on-year — even with investment merely slowing the rate of loss to 2-4% per annum.

And that investment comes at a cost. Unlike Norway, the British state does not hold a stake in the major gas producers. And, while we get tax receipts from production in our own country, we don’t get any preferential prices for consumers. In the UK’s highly liberalised market framework we allow domestic production to be sold at volatile global market rates — otherwise, oil and gas companies will stop investing.

To escape this trap, the UK must focus on our gas dependency more in the short term so we can worry about it less in the long term. We must develop a strategy for a gradual gas phase-out, as we did with coal, by making the alternatives less expensive. That is now the task: a new, economically rational managed decline of gas centred on affordability.

The answer lies not just in scraping the barrel of depleted North Sea reservoirs with tie-backs (the myth we can ever return to self sufficiency is just a distraction); but in forging a new class of strategic energy partnership where we seize the moment and allow ourselves to question today’s norms.

Focussing on the cost challenge

What then should the Norway-UK energy dialogue focus on? Longer term, clean future energy systems such as offshore wind make sense. But there is an elephant in the room: the cost of energy. The UK’s massive reliance on gas, especially for winter heating, will not diminish quickly. And a lot of that gas arrives from Norway, which enjoys huge profit margins from sales to meet British demand.

Around half of the cost of UK consumer gas bills is determined by upstream commodity costs. And while it is common to attribute high prices to abstract ‘global markets’, we must continually ask what more can be done to protect consumers from excessive rent taking. That includes taking a long hard look at our relationship with Norway.

Because in a world where previously unthinkable things are happening to global trade, courtesy of populist politics and transactional foreign policy, there is a need and an opportunity to question norms.

The Art of the Deal: Challenging the status quo

Rather than pursuing a Trumpian ‘UK first’ negotiating stance, London and Oslo could reframe the priorities of their bilateral energy trade relationship for mutual benefit. Signing new long-term contracts for Norwegian gas supply would reduce the UK’s exposure to volatile market prices, while offering Norway guaranteed demand and a price floor for gas it currently sells on the spot market.

The timing for a frank conversation about affordability and demand certainty couldn’t be better as global gas prices look set to soften significantly thanks to a flood of new LNG entering the market. The question is how to leverage this to both parties’ advantage.

A parallel diplomatic initiative could offer a sweetener: preferential UK government-backed critical energy infrastructure investment opportunities for capital investments from Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund. Examples could include boosting UK clean power generation, bolstering grid infrastructure, accelerating electrification, and, in the short to medium term, increasing the UK’s dismally low gas storage capacity. What we should focus less on are the illusory promises of CCS and the ‘hydrogen economy’ which will always be more expensive than the alternatives.

Gas storage: the UK’s Achilles heel (expand)

One of the UK’s greatest physical energy system vulnerabilities is its extremely low gas storage capacity: just ~3.2 billion cubic metres (Bcm) or 19 days of supply. The paucity of this provision is apparent when compared to countries like Germany, which boasts ~25.6 Bcm or 119 days of supply. This lack of capacity leaves the UK acutely exposed to short-term price spikes; a nice situation for commodity market speculators but bad for end consumers.

The energy sector is littered with examples of where leaving everything to the market proved unwise. Underprovision of gas storage is a prime example. For years, market prices did not support gas storage investments so facilities were shuttered and capacity dwindled. Before Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine, energy ministers would routinely cite the UK’s capacity to import expensive LNG from global markets as adequate security (which it is not).

But loss of Russian pipeline gas triggered a global scramble for LNG and unprecedented price spikes in 2022-23, allowing well-positioned traders and commercial players to sell long physical gas/LNG positions into red-hot spot markets — and gouge consumers in the process. Extra gas storage would not have avoided the energy crisis, but if managed responsibly it might have mitigated the worst impacts on households.

De-risking gas storage investment

The economics of gas storage in the UK are challenging as a pure play investment made by the private sector. However, gas storage — to the extent that it can take the edge off gas market volatility — offers strategic value to both the UK and the Norwegians. Especially as high energy prices are being weaponised in the UK, leading to increased political risk; policy stability on both sides is better for business.

To facilitate investment in storage infrastructure, the UK has several levers it can pull to de-risk projects. The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), the UK’s oil and gas regulator, could be instructed to offer regulatory incentives such as fast-track permitting.

The government could task Ofgem, the energy regulator, to create a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model for new storage sites. And the Future System Operator could be directed to procure storage services through long-term contracts to balance the energy system, creating a predictable business case for the lifetime of the asset.

Strategic gas reserve

De-risking storage in this way reduces the commercial imperative to exploit seasonal gas price arbitrage to recover capital investment, allowing storage sites to be managed and operated as a strategic reserve (rather than as a purely commercial play).

Large gas storage investments backed by UK sovereign guarantees could be an attractive proposition for investment from Norway’s massive £1.5 trillion Sovereign Wealth Fund, which tends to seek stable, long-term, value-accretive returns. There is also a virtuosity to using this fund in this way: UK consumers have paid into Norway’s ‘rainy-day’ oil fund over decades via purchases of Norwegian pipeline gas.

Increased economic regulatory oversight and intervention by governments in the gas sector is not without precedent; Norway itself recently brought petroleum pipelines into public ownership to better control transportation costs and maintain export competitiveness. UK gas storage should be considered as part of a comprehensive affordability agreement.

The hydrogen distraction

Perversely, while Britain’s fundamental natural gas storage vulnerability remains unaddressed, political and commercial focus is being diverted towards a speculative hydrogen future. Centrica Energy Storage, which owns and operates Rough, the UK’s largest storage facility currently operating at half capacity, is actively exploring repurposing the site for hydrogen storage.

Hydrogen is a notoriously inefficient energy carrier, with round-trip system losses as high as 70% when accounting for energy lost during conversion. The widespread use of hydrogen for seasonal storage remains at best a distant prospect. To prioritise this over solving a known and present energy security risk and pricing challenge is a profound misplacement of strategic priorities.

Perfect time for a reset: Demand = leverage

The current energy market environment may present a unique diplomatic opportunity for a reset of the relationship between the UK and Norway.

With an unprecedented wave of new LNG supply entering the global market between now and 2030, market prices for gas traded on UK and European exchanges are poised to plummet. Futures markets are already pricing in a 30% drop in wholesale gas prices over the next three or four years, and further declines are anticipated as new supply enters the market more quickly than demand is able to absorb it.

At current prices, Equinor is earning roughly €10 billion on the ~31 Bcm of gas it exports to the UK every year. A 30% drop in wholesale gas prices would erase approximately €3 billion from Equinor’s annual revenue stream from the UK. At 50%, the revenue loss would be greater than €5 billion. This stark projection underscores the significant financial vulnerability they face from a potential global LNG glut.

The UK’s negotiating position is strengthened because the market itself is poised to inflict a severe financial wound. Offering a stable, lower-margin (far closer to production cost) supply contract, in exchange for strategic investment opportunities, represents a way for Equinor to mitigate a potential €5 billion annual headwind and secure a more predictable, long-term revenue stream from the UK market.

What’s in it for Norway?

Equinor is highly exposed to gas market prices, with only a fraction of its production under long-term contracts. This gives the UK leverage: the offer of new long-term sales and purchase agreements (SPAs) with a price cap and floor could be tempting on the cusp of a new structurally soft gas price regime.

Norway’s state-controlled oil and gas company sold 63.6 Bcm of natural gas in 2024. Judging from publicly known long-term contracts (with European buyers such as SEFE, OMV, PGNiG, Centrica, BASF and RWE) only around a third of that supply is tied up in contracts. The rest — we estimate roughly two-thirds of its gas output — is sold through Equinor’s trading arm on a merchant basis, meaning prices fluctuate with market conditions.

Heavy spot exposure is a double-edged sword. When hub prices soar, the company’s coffers swell. When prices collapse, its earnings drop. The flip side is flexibility: Equinor still has plenty of uncontracted gas available that could, in theory, be committed to new long-term SPAs if buyers want more predictable pricing or supply security.

The headline numbers are enough to show that most of Equinor’s gas remains merchant, leaving it highly responsive — and vulnerable — to market swings. The point is that there is an opportunity to link the UK’s essential, on-going need for affordable energy to Norway’s desire for guaranteed, long-term market access.

A shared plan that helps insulate the UK from global gas prices could provide Norway with a more certain demand curve from the UK, enabling them to plan their own orderly transition.

New pragmatism = win-win

With market dynamics and political undercurrents shifting rapidly, business as usual is not an option for the UK or Norway. A new pragmatic approach would reorient our energy interdependence towards a mutually beneficial trade relationship — but it will require burning down some sacred cows.

The UK must accept that the country will need gas for a while longer. Instead of pretending the market will fix it, the government must proactively recalibrate existing alliances around the singular objective of energy affordability. To achieve the desired outcome, it must make Norway an offer it can’t refuse, and build out strategic resilience (storage) along the way for good measure.

By leveraging strong political ties to Norway to frame gas supply and inward investment as a partnership in affordability, the UK can achieve prices closer to production costs in the future and lock in the volume security needed to reduce pressure on consumer bills.

Norway, for its part, must accept that post-Ukraine windfall rents from volatile markets are finite and politically risky and having benefited from them thus far they need to deploy those windfalls in strategic investments.

By accepting cost-plus pricing on new contracts, they trade some short-term margin for long-term demand security and a predictable revenue stream for their remaining resource base, shielding the state from lower rents during the coming LNG supply glut. This approach also provides a model for responsible resource stewardship as they, too, face depletion.

In addition, Norway gains exposure to strategic UK infrastructure investments on preferential terms that deepen the relationship with their biggest energy customer.

The combined effect of softer upstream commodity prices and reduced exposure to price variability via long-term SPAs and investment in storage will flow through to a more economically secure and affordable energy system in both countries.

Ultimately, North Sea gas is a finite resource and it will run out. Therefore, we need policy and political stability to chart a course away from a dependence on it — but in the short term that will only happen if we focus on keeping it an affordable commodity. Governments in London and Oslo stand to benefit by taking control of their intertwined energy systems for mutual benefit.

Author bios (click to expand)

Bryony Worthington, The Baroness Worthington, is a British environmental campaigner and life peer who helped draft the landmark UK Climate Change Act 2008 and later founded the NGO Ember (formerly Sandbag) to accelerate the shift to clean energy. She was appointed to the House of Lords in January 2011 and now sits on the cross-bench, bringing her expertise in energy, climate and policy to the UK Parliament. She is currently on a leave of absence with her family in California.

Harry Benham is a British energy industry veteran with over 30 years of upstream experience at BP and Shell, who now serves as Executive Director of Ember and Senior Advisor to Carbon Tracker Initiative, focusing on the energy transition. During his oil and gas career he held senior roles such as Vice President/Procurement Director for major projects, and has since turned his expertise to advising on decarbonisation, policy and financial risk in the global energy system.

Seb Kennedy is a lifelong energy journalist and market analyst, and founding editor of Energy Flux. Since 2008, Seb has written for a wide variety of energy news outlets, and has held senior editorial roles in energy trade press ReNews, management consultancy Gas Strategies, and climate analytics non-profit Transition Zero. He has also freelanced for The Spectator, The Daily Telegraph, Energy Monitor, and Cornwall Insight, among others.

Enjoyed this article? Sign up to Energy Flux to get original, thought-provoking, 100% independent energy market analysis direct to your inbox

Member discussion: UK-Norway gas trade: Time for a New Deal?

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.