The rise of the middlemen

Why are traders gobbling up LNG in a moribund market? | EU LNG chart deck: 27 Nov-8 Dec 2023

Trade in liquefied natural gas (LNG) will soon be dominated by middlemen. ‘Portfolio players’ with heroic demand assumptions are buying up startling volumes of LNG amid a notable flatlining in winter gas consumption in Europe. International oil companies and trading houses are going long on an expensive fuel that most analysts believe will be in acute oversupply in just a few short years — or perhaps sooner. But a closer inspection suggests there is method to the middlemen’s madness.

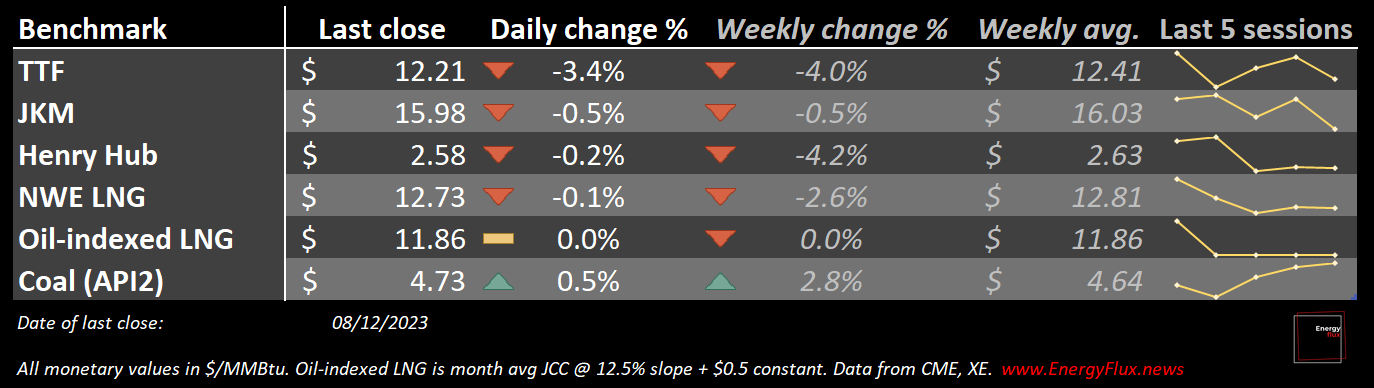

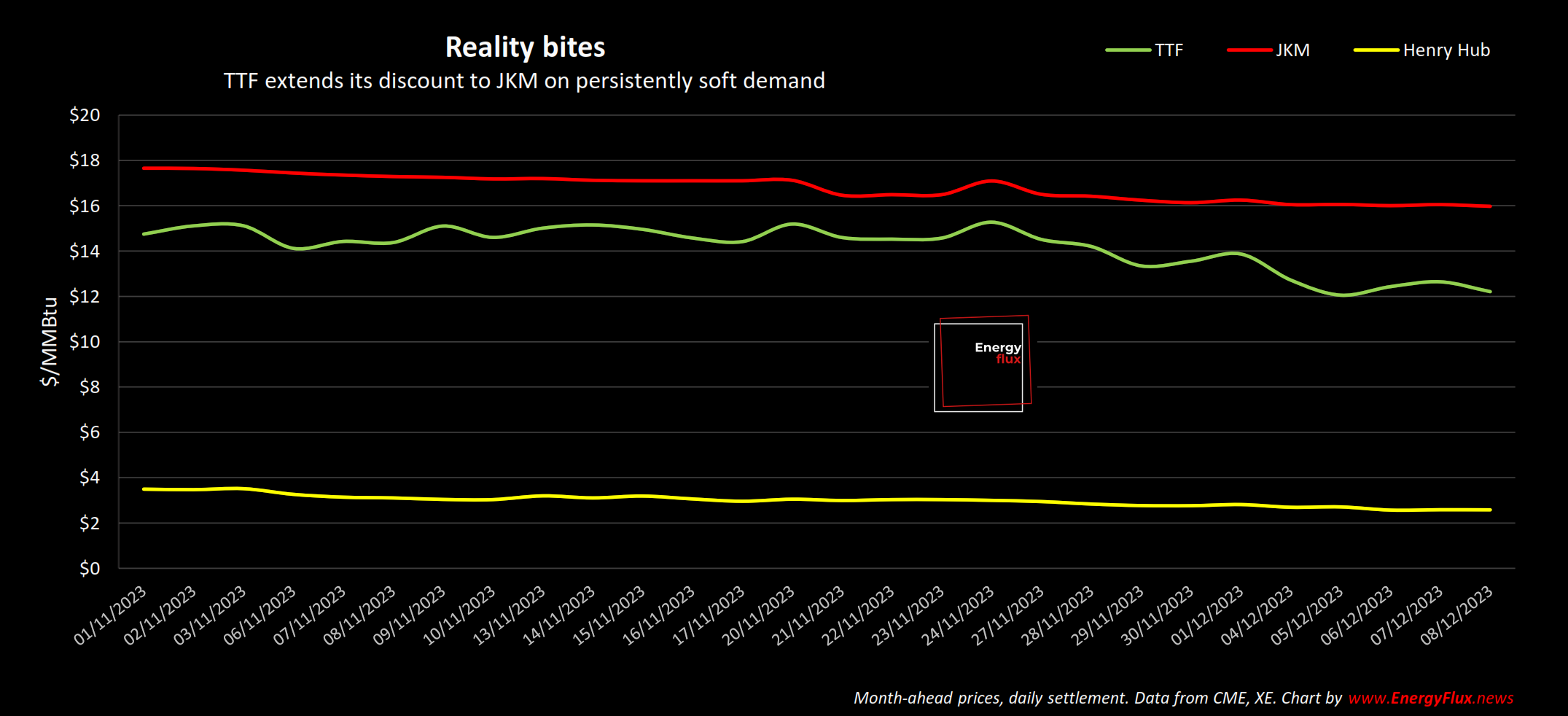

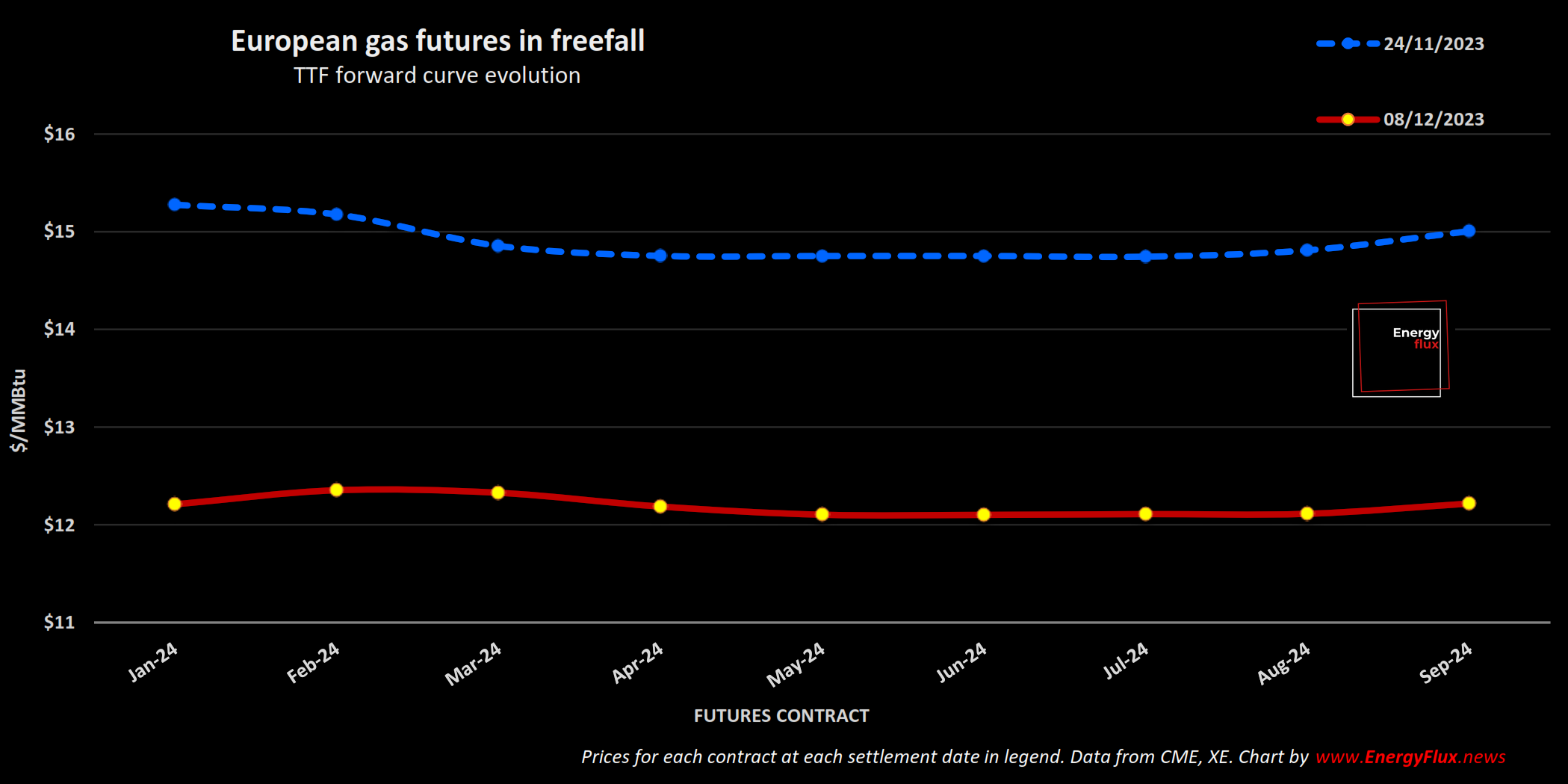

First, let’s take stock of the market. Europe’s supposed ‘post-Russian gas crisis’ is deflating before our eyes under the weight of stagnant winter demand. Prices on Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF, the European benchmark for natural gas), have fallen 20% in the last two weeks alone to the equivalent of $12 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) — despite a brief cold snap that all but drained the UK’s meagre gas stocks.

Analysts are even predicting that a mild, windy El Niño winter could see the February and March 2024 TTF contracts dipping below the summer months, minimising storage withdrawals in late February.

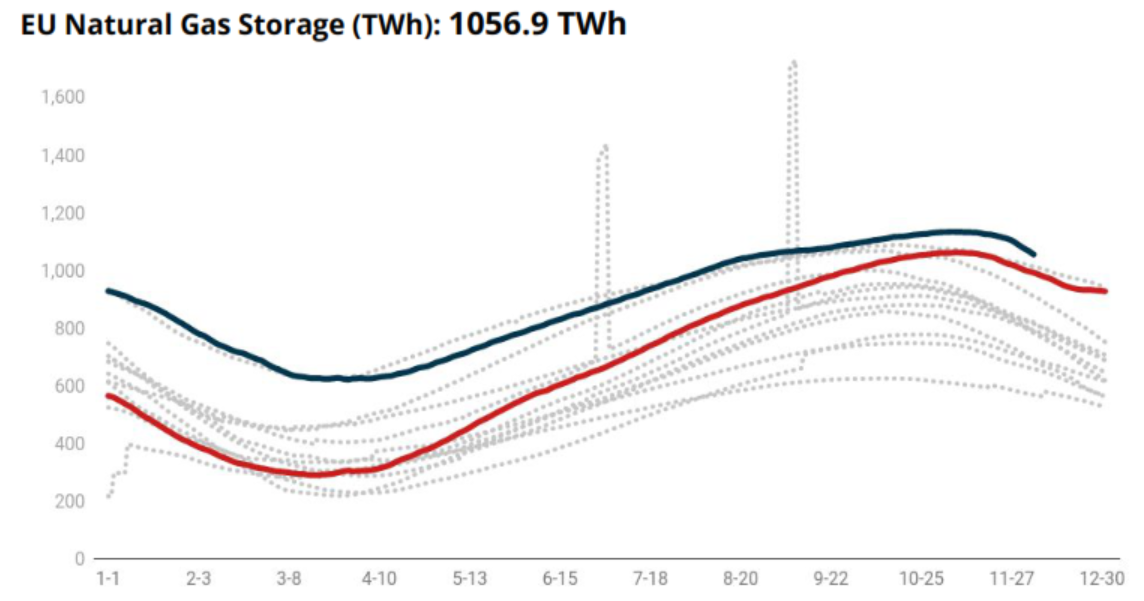

If this happens, Europe will be well positioned to again coast through the restocking season and be as well-placed as it was this year heading into winter 2024/25.

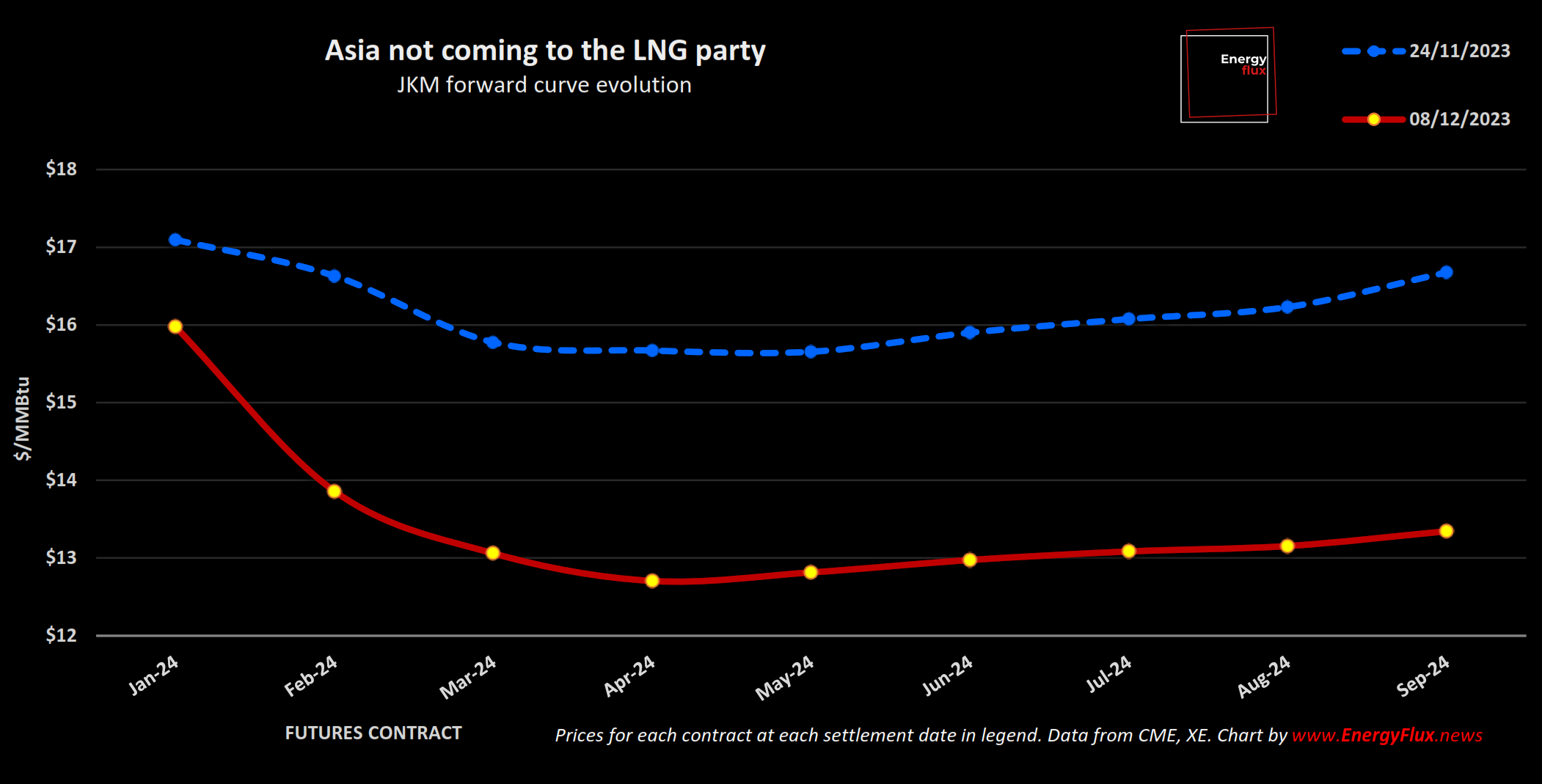

Anyone looking to Asia to rain on this parade of European gas market tranquility is likely to be disappointed. The Japan-Korea Marker (JKM, the North Asian spot LNG benchmark) has also deflated since the last EU LNG chart deck — albeit not quite as dramatically. The front month (Jan-24) is still trading at $16/MMBtu, with the curve strongly backwardated throughout Q1 2024.

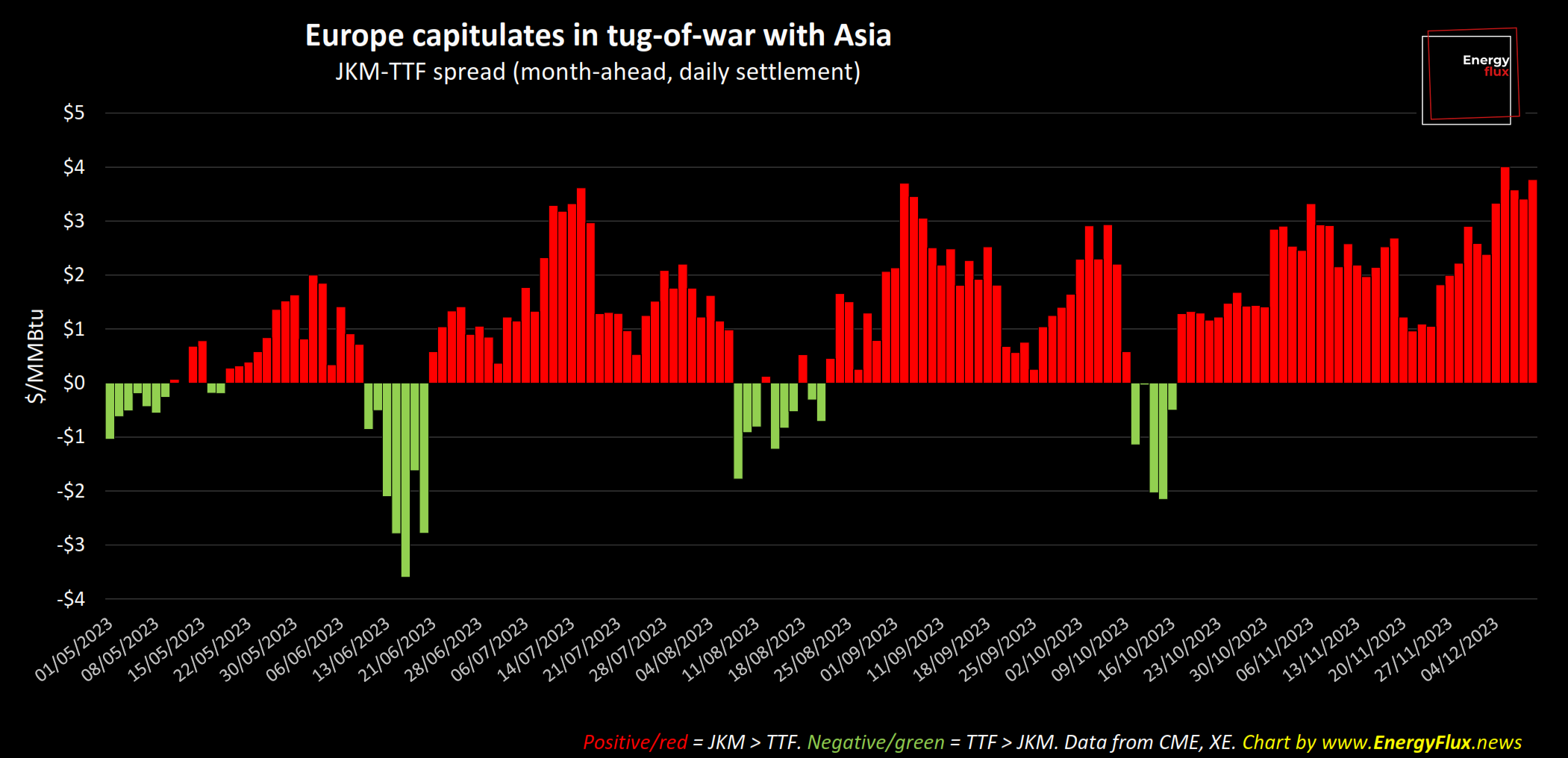

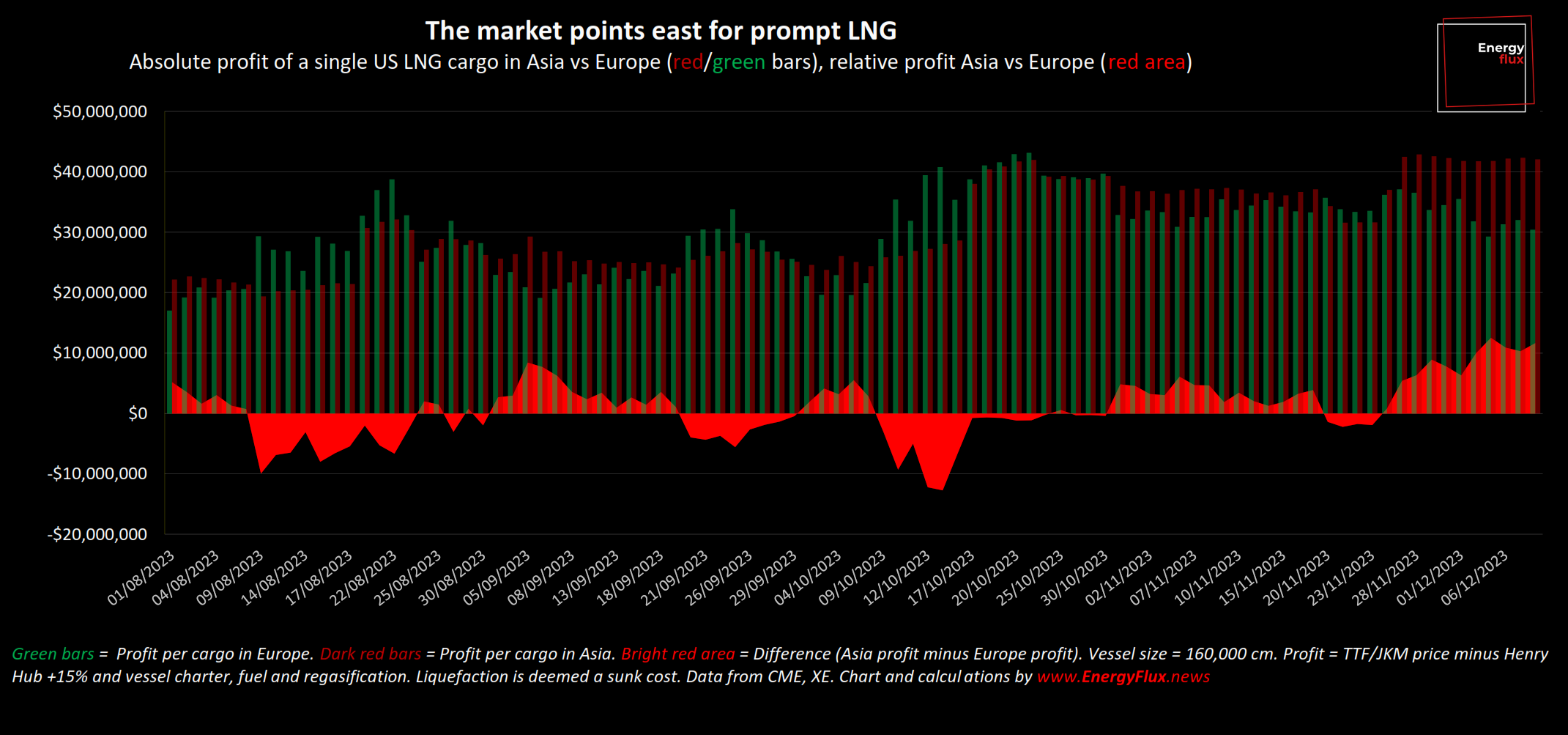

The steeper decline on TTF has reasserted a strong ‘Asian premium’ for LNG. The JKM-TTF spread breached the equivalent of $4/MMBtu last week, a level not seen since January this year. But don’t be mistaken — Asian buyers are not rushing out to tender. This is merely confirmation that Europe is retreating more quickly from the market because it literally has nowhere to put the gas.

The cold snap that drained the UK’s tiny gas storage capacity made barely a dent in plentiful EU gas stocks, which still stand at 93% full — well above the 10-year average for this time of year.

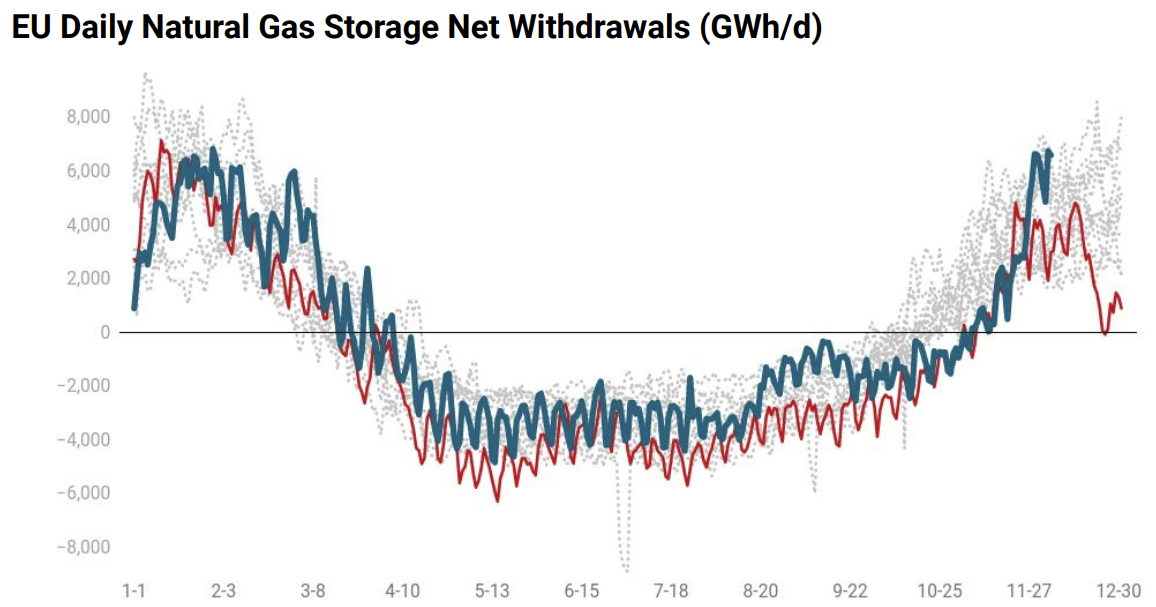

The brief spell of colder weather did trigger an uptick in withdrawals from EU storage. Data from Gas Infrastructure Europe, visualised by, show daily net withdrawals spiking to some of their highest ever levels for early December — presumably because the lack of Russian pipeline gas leaves no alternative than to use stored gas to balance the market during cold snaps.

And yet TTF still fell by one-fifth while this happened. The result is a steady deterioration in the profitability of shipping spot LNG from the US Gulf Coast to Europe relative to Asia. The margin on a standard cargo carrying 160,000 cubic metres of US LNG is now less than $30 million — a two-month low.

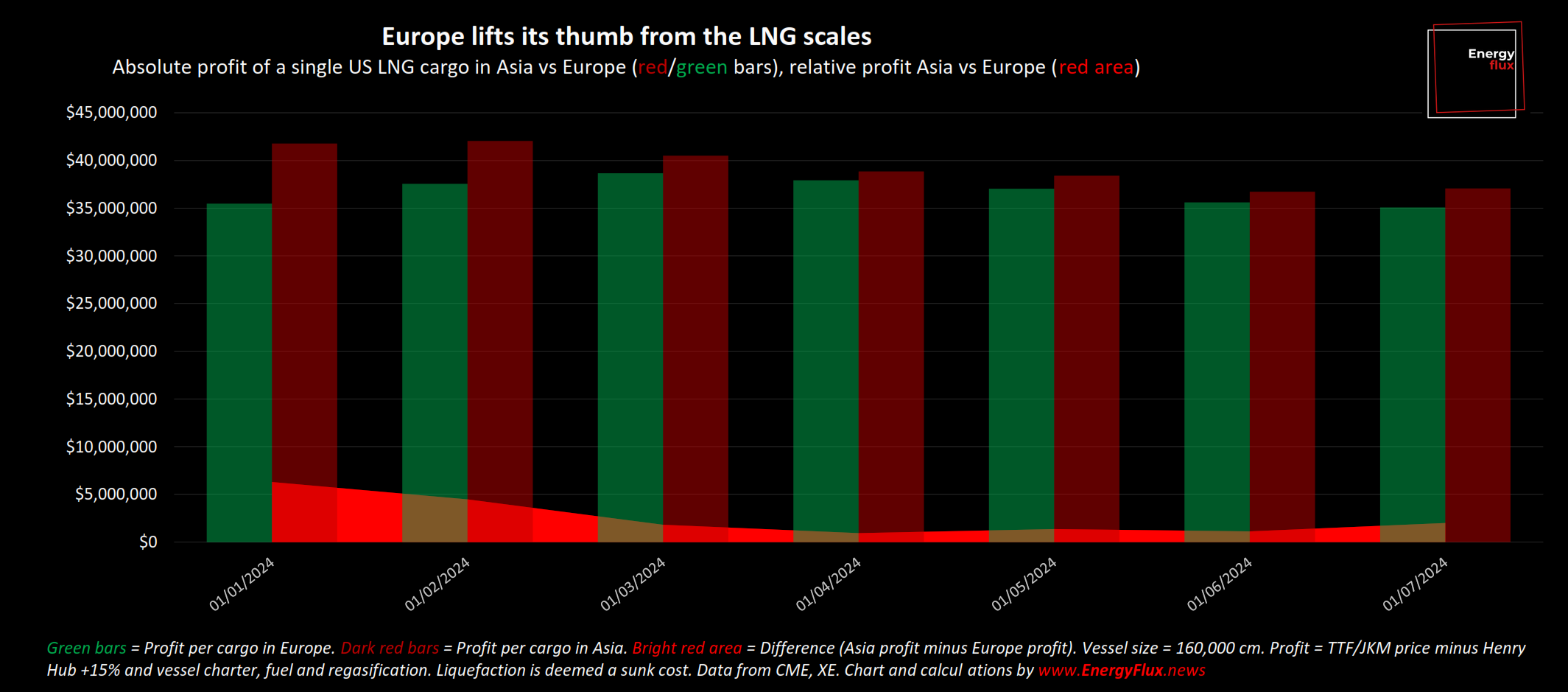

The market does not expect that to change much over the coming months. On paper at least, Asian netbacks are now edging out Europe for the foreseeable future (although these calculations do not take into account the severe bottlenecks on the Panama Canal that are forcing some vessels to sail all the way around Cape Horn).

So why, considering all the bearishness in a market that is only going to get more grizzly as new supply from Qatar and the US comes onstream, would anyone want to sign up for more LNG offtake without first securing a firm, profitable outlet for those volumes?

YOLO-ing on LNG price risk

Australia’s Woodside last week inked a 20-year sales and purchase agreement for 1.3 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) from Mexico Pacific LNG, a new export plant fed by US shale gas that is slated to come online during the post-2026 glut. This is the latest in a long string of SPAs between North American LNG exporters and ‘portfolio players’ — companies that both produce their own LNG and buy and resell volumes from other exporters, or traders and aggregators such as Trafigura and Vitol that bring commodities to market.

These middlemen have signed offtake deals for no less than 65% of the 100 mtpa of new LNG export capacity under construction in the US, Mexico and Canada, according to Poten. They will need to find other buyers for their cargoes at strike deals at the best terms available. If none can be found, they will rely on the spot market — which, as is clear to see, is not showing much sign of improvement between now and the date when this capacity is due to enter the market.

How can we explain this? Why would well-resourced and sophisticated traders go long on a fuel under a pricing regime that is handsomely profitable today but at growing risk of converging with — or even falling below — the price redeemable in LNG-importing countries?

Force-feeding the market

There are several theories to consider. The least flattering was alluded to in my opening sentence: hubris. The loss of Russian pipeline gas sent a rush of blood to the head of traders, who raked in unspeakable profits as Europe pivoted sharply to LNG to fill the gap. Perhaps there is a belief that, for as long as a negotiated peace settlement in Ukraine remains untenable, demand for spot LNG will be robust — regardless of how much new supply enters the market?

The LNG market is highly cyclical and prone to sharp price swings because the fuel is not as fungible as oil, which is a far more financialised commodity with greater ability to swap cargoes and delivery location, and which does not gradually boil off in transit. Amid war and geopolitical turmoil, maybe there is a belief that ‘this time it will be different’?

This might offer a partial explanation. But perhaps there is a greater fear hanging over the middlemen: that today’s prices are stifling growth in demand for their heralded transition fuel?

TotalEnergies CEO Patrick Pouyanné alluded to this fear in an interview at COP28 last week, telling Bloomberg:

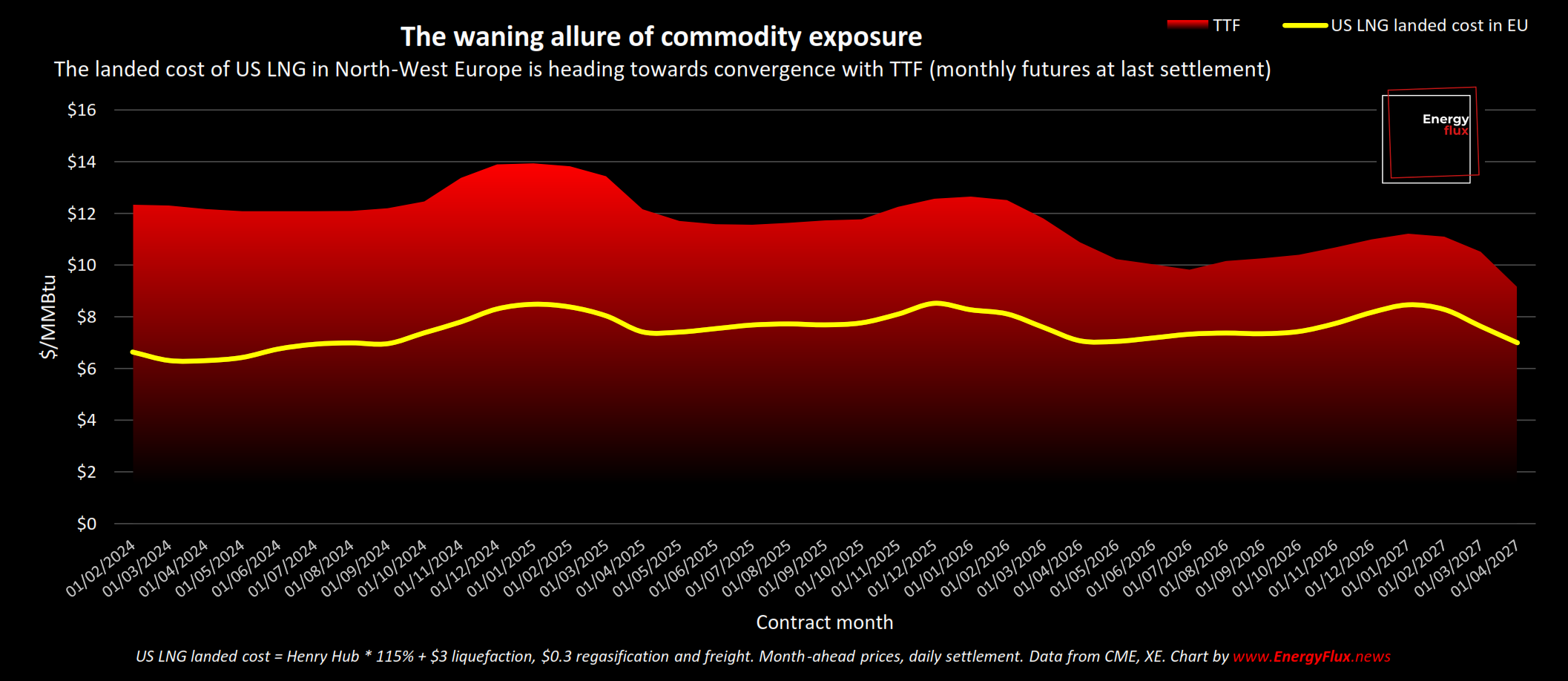

“We know that when we want to grow LNG [demand], we want to have enough supply in order to have a price more in the range of $8-10 per MMBtu because then it is acceptable for the Indian economy, the Thai economy, Bangladesh or Japan, even the Korean economy.”

If ‘genuine’ LNG buyers are unwilling or unable to sign enough long-term sales and purchase agreements (SPAs) to get new liquefaction projects financed, then that burden falls on the oil industry’s titans — the biggest, most creditworthy corporates — to do the heavy lifting.

This means lengthening portfolio exposure to LNG, and carrying the risk that these contracts become less profitable over time. Currently, the futures market is pricing in the possibility of that happening — although not to the extent that US LNG becomes unprofitable in Europe, even in 2027.

Threading the needle

LNG has two big price problems: it is expensive per unit of energy compared to other fuels, and its main application — power generation — is a highly competitive field that is being devoured by zero marginal cost renewables. The ‘sweet spot’ is a narrow price band: too high and it becomes uncompetitive, too low and it barely covers the cost of production, shipping and regasification.

The middlemen are targeting growth markets that are highly price sensitive, such as Thailand, Vietnam, India and Bangladesh. Their (apparent) strategy is a tricky balancing act: sign enough SPAs to bring new supply to market and bring down prices to a level that stimulates demand.

US LNG flirted around the margins of profitability in Europe for several years pre-Covid, and when countries locked down it made no economic sense to keep liquefying American shale gas for export. Widespread plant shut-ins occurred and offtakers paid hundreds of millions of dollars in penalties for cargo cancellations.

The magic of sunk cost accounting might neuter fears of a repeat of 2020. But as one analyst put it to me, the way the coming wave of new supply is shaping up, “the only ones that will make money are the LNG vessel owners”.

Nice work if you can get it

For now, there is still enough much money to be made in LNG trade to make 2027 feel a long way off. Three years is an eternity in today’s energy markets, and traders’ bonuses are determined by the profitability of their decisions over the preceding 12 months.

Swiss trading house Trafigura has just tripled its dividend to $5.9 billion after notching up another record-breaking annual profit. Spread across the company’s 1,200 top traders and executives, that’s an average payout of nearly $5 million per person. With more seven-figure bonuses to be earned in 2024, why would any middleman think twice about signing up for more?

Trafigura does not expect the tide to turn on LNG any time soon, although it did highlight a cooling off in its annual report. Its balance sheet shrank by 15% to $83 billion, “mostly driven by the decrease in the valuation of our long-term LNG contracts and related margin requirements from brokers and exchanges, as a result of the drop in natural gas prices in Europe”.

While the medium-term outlook points towards a weakening gas market, this is still an exceptional time to be lifting and trading LNG and other commodities. I’ll leave the final word on this to Richard Holtum, Trafigura’s head of gas, power and renewables, who was notably silent on what the second half of the decade might look like:

“Looking ahead, although 2023 brought a gradual softening of gas and power prices in Europe on the back of a mild winter, lower demand and increased LNG imports, we expect markets to remain turbulent and prone to spikes in 2024.”

Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 11 December 2023

Enjoyed this post? Get independent gas and LNG market commentary from Energy Flux delivered straight to your inbox:

More from Energy Flux:

Member discussion: The rise of the middlemen

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.