Europe’s pyrrhic gas victory

DEEP DIVE: War has taken a $1 trillion toll on European gas consumers

Europe survived last winter with unexpected ease. Mild temperatures helped, as did lacklustre Asian appetite for liquefied natural gas (LNG) and unprecedented conservation measures. There was much relief when wholesale prices fell below ‘pre-invasion’ levels in January, and this sentiment has intensified as Europe’s underground gas storage tanks swell. Mission accomplished?

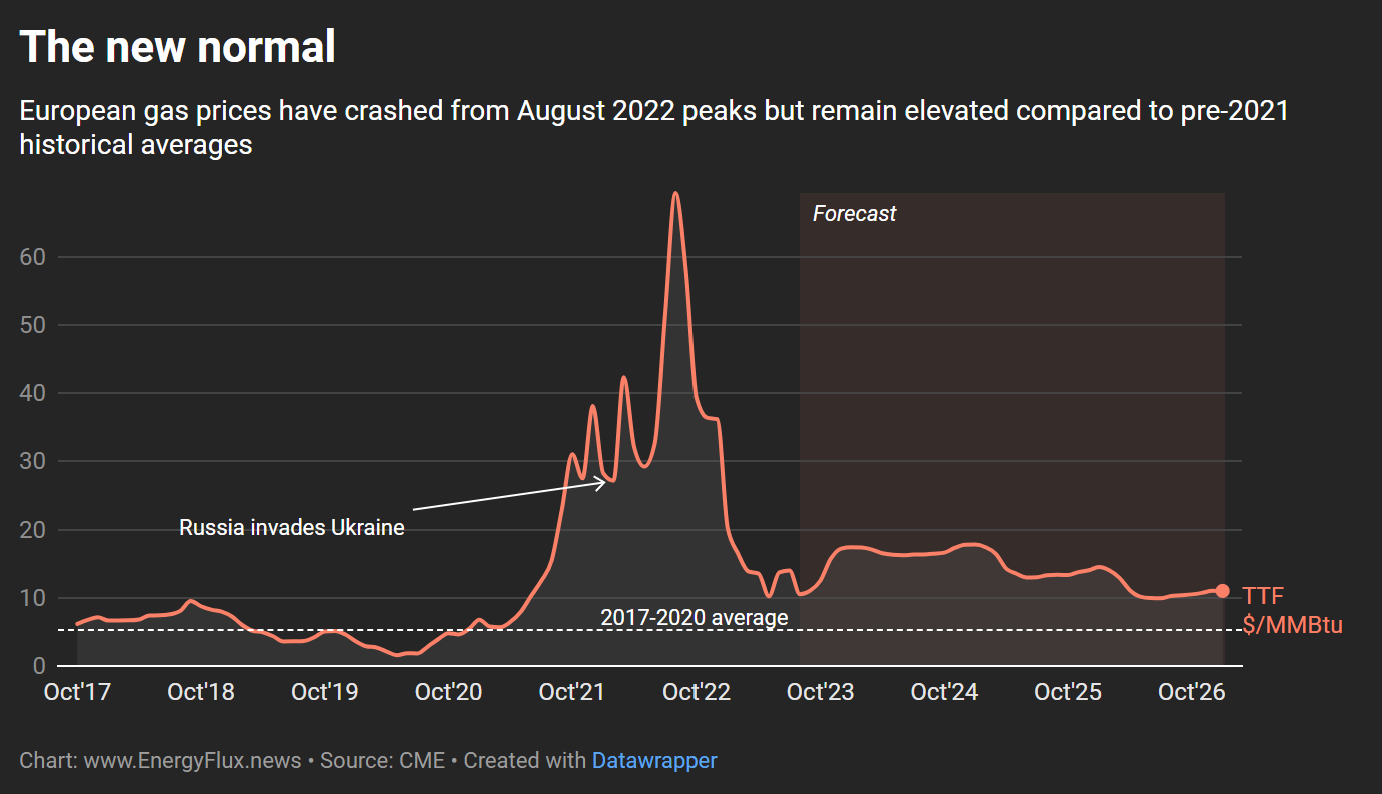

EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson seems to think so. She made some bold remarks about turning the tables on Putin and ending reliance on Russian gas in an interview with Politico. Europe’s immediate energy situation is certainly much better than many feared just a few months ago. But this does not hide the fact that Europe is still paying significantly more for gas than it did prior to 2021, when Russia began meddling in European energy markets ahead of the full invasion of Ukraine.

Gas prices on the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF, the European benchmark) averaged $5.31/MMBtu over the 2017-2020 period, whereas today the front-month contract is trading at $9.44/MMBtu, rising above $17 for delivery in January and February 2024.

Trillion-dollar albatross

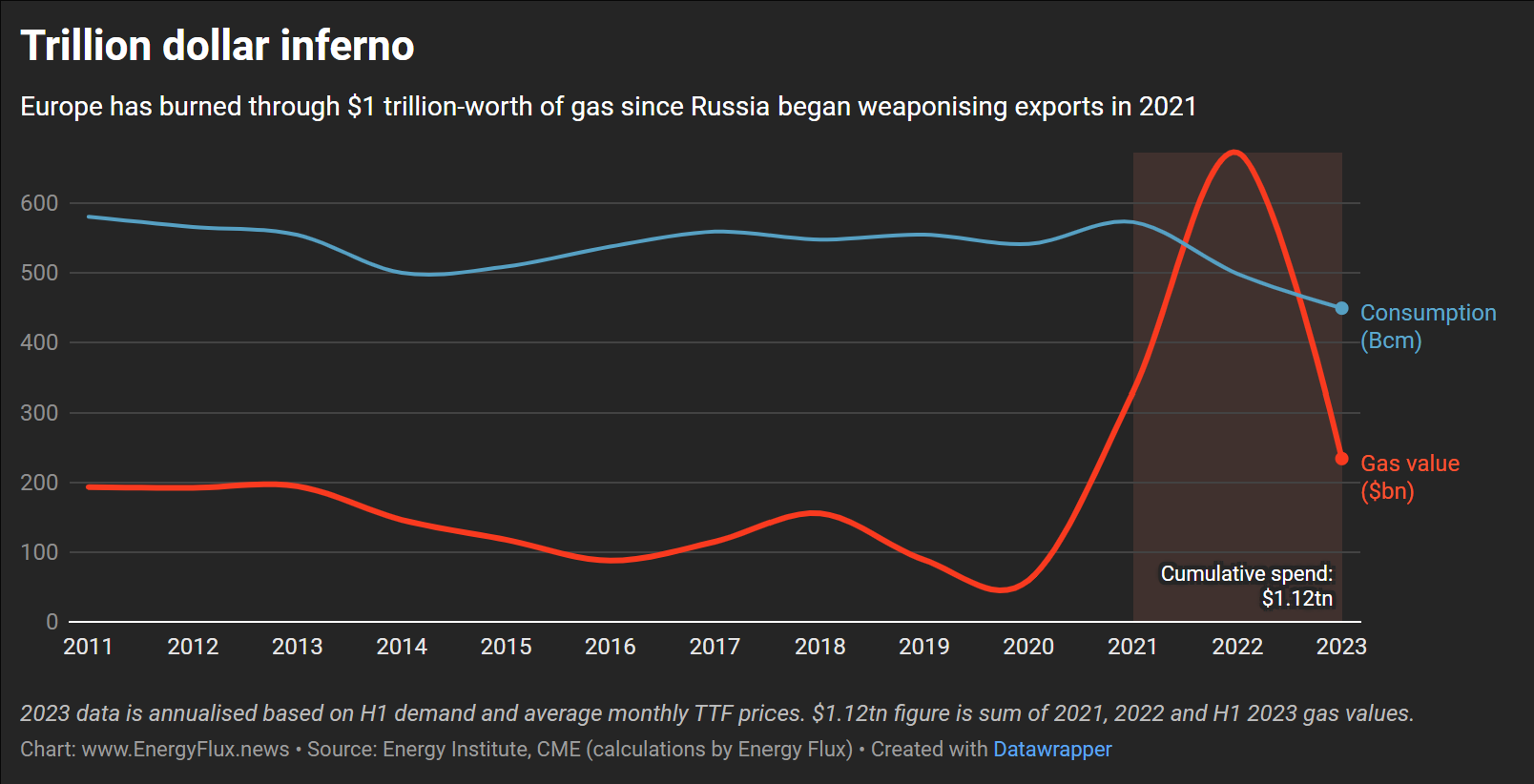

These elevated prices are hard to absorb because European consumers are still burdened with an eye-watering cost overhang. Believe it or not, Europe has burned through more than a trillion dollars’ worth of natural gas since Russia began weaponising pipeline exports in preparation to invade Ukraine.

Yes, you read that right: the value of gas consumed across the European continent since 2021 currently stands at $1.12 trillion, and structurally higher prices could see that amount rise by a further $600 billion by mid-decade.

Calculations by Energy Flux based on the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy and exchange data offer fresh perspectives on the toll of wartime gas pricing on Europe’s financial health. Europe spent a decade’s worth on gas in just two and a half years, even though consumption fell to a 28-year low in response to scarcity prices.

A gargantuan debt is attached to gas held in storage, which means more pain for consumers and an enduring drag on European industrial productivity. Restocking with LNG at the height of the market stifled Europe’s energy-intensive industries and rebased the continent around a high-cost, low-demand energy economy paradigm.

Quantifying the burn

First, let’s break down the numbers. Fair warning: this is a simple calculation based on high-level data, so has a low confidence level and high margin of error (see footnote1). That said, it gives plenty of food for thought. So, with the health warning duly administered, here goes.

Gas consumption across the continent of Europe – the EU27 plus Norway, the UK, Turkey, Ukraine, and other non-members – dropped 13% to 499 billion cubic metres (Bcm) in 2022. This was the smallest amount of gas consumed in the region since 1995, with steep year-on-year declines seen in Finland (-48%), Sweden (-30%), Ukraine (-29%), Latvia (-30%) and Denmark (-28%). Gas burn in Germany, Europe’s biggest gas market, fell by 15%.

Month-ahead TTF averaged $38/MMBtu in 2022 and $16/MMBtu in 2021. If we assign these prices to the volume of gas consumed each year, then Europe’s gas consumption can be crudely valued at $673 billion in 2022 and $330 billion in 2021.

EU-only gas demand over the first six months of 2023 fell by 17.7% below the 2017-2022 average. Applying that 17.7% derating factor to continent-wide demand over the same period, pan-European consumption can be estimated at 225 Bcm of gas in the first half of this year, when prompt TTF averaged $14.50/MMBtu. Multiplying volume by price puts the value of H1 2023 gas consumption at $117 billion.

Add these figures together, and the total value of gas burned across the continent of Europe over the last 30 months comes in at a grand total of $1.12 trillion. This is comparable to the value of gas burned over the preceding decade to 2020 ($1.35 trillion).

Thanks for reading. Please support Energy Flux by sharing this post

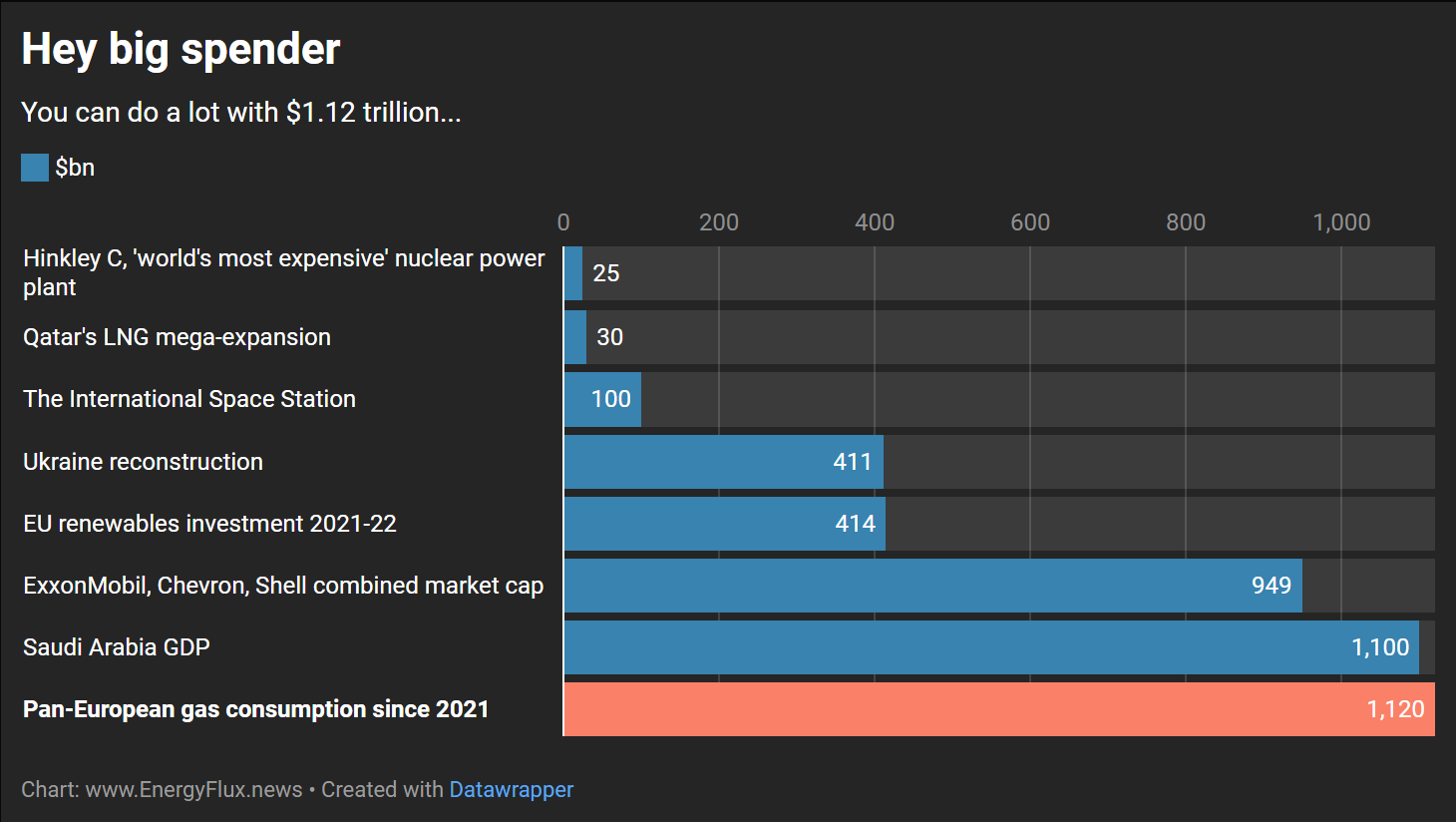

Epic hangover

For perspective, $1.12 trillion exceeds the GDP of Saudi Arabia, and is more than the combined market capitalisation of ExxonMobil, Chevron and Shell. It dwarfs the amount that Europe invested in clean energy over this period ($260 billion in 2021 and $154 billion in 2022, per the IEA), and is more than double the estimated $411 billion cost of post-war reconstruction in Ukraine.

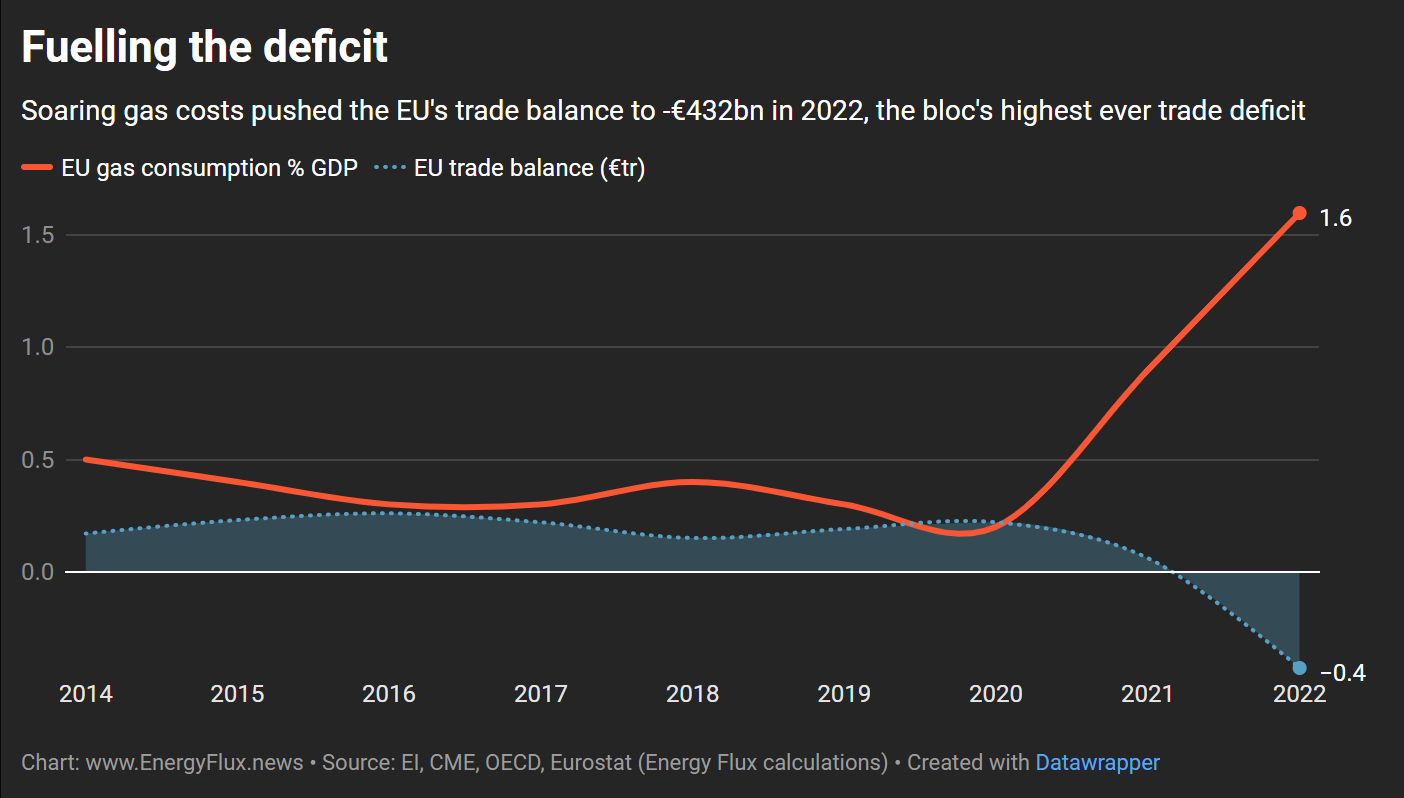

Burning through one trillion dollars’ worth of gas pushed the EU’s trade deficit to a record -€432 billion in 2022. This is a huge macroeconomic drain and a major reversal of recent trends. Gas consumption as a percentage of EU GDP had been declining steadily from around 0.5% in 2014 to hit a low of just 0.2% in 2020, the year of pandemic lockdowns and cratering global energy consumption.

Russia’s pre-war manipulation of European gas markets in 2021, and the wild price gyrations triggered by its full invasion of Ukraine, slammed that trend into reverse. EU gas consumption as a percentage of GDP shot up to 0.9% in 2021 and again to 1.6% in 2022.

Costing Europe’s LNG binge

The trillion dollar figure includes pan-European domestic gas production and imports (both by pipeline and seaborne LNG). Domestic gas volumes (in theory) attract production levies and taxes that flow back into state coffers. European gas production also supports jobs, so the economic ‘value’ to Europe of consuming expensive gas cannot be considered entirely negative (although for unhedged consumers it is all cost and no benefit).

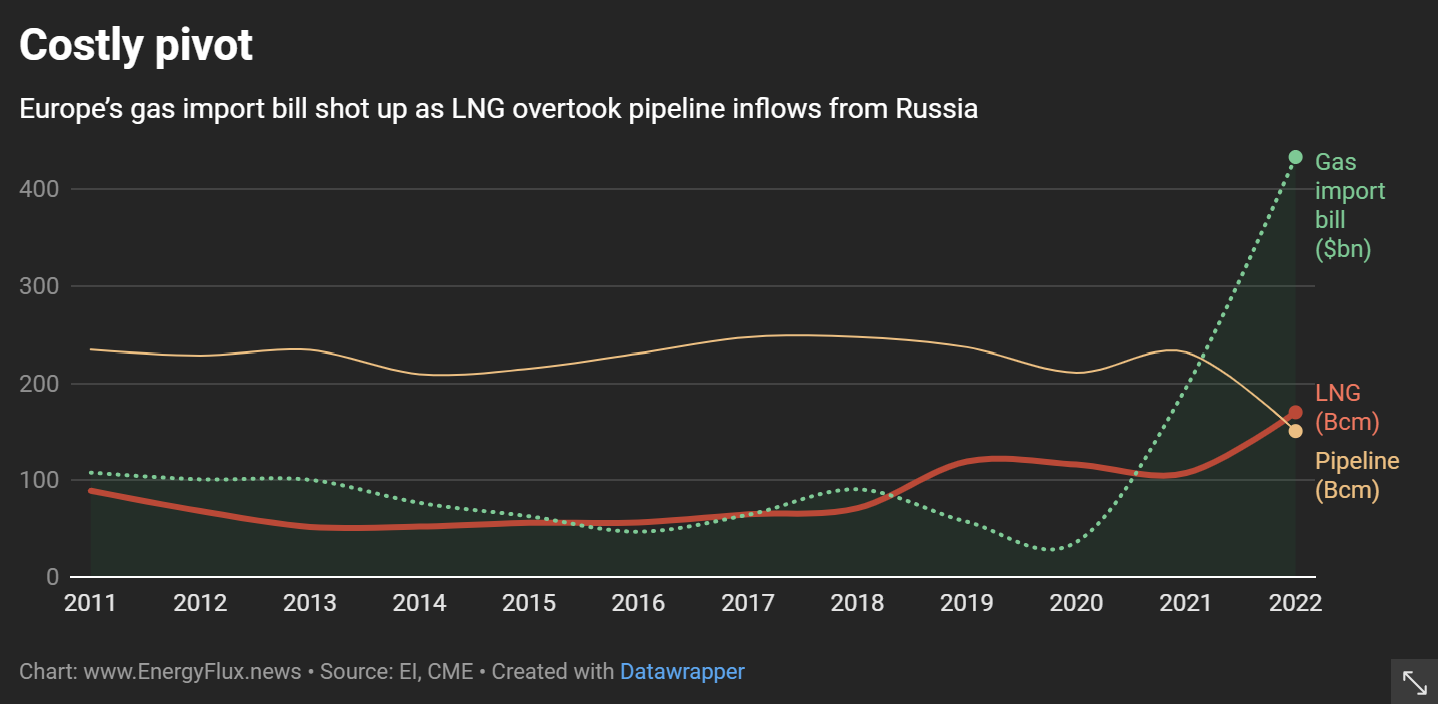

The import bill (pipeline + LNG) is the most interesting element because it represents an outflow of wealth from European economies into gas exporting nations, so can more appropriately be described as a ‘cost’ to Europe.

Using the same data sources and methodology as above, Europe’s gas import bill can be estimated at $702 billion since 2021 ($196 billion in 2021, $433 billion in 2022 and $73 billion in the first half of 2023). These are huge increases on 2020, when Europe spent $36 billion on gas imports. Over 2011-2020, Europe’s total gas import bill was $744 billion, or on average $74 billion per year.

Import costs spiked even though Europe imported less gas overall. LNG imports increased by 63 Bcm (+58%) in 2022 but did not replace Russian inflows in their entirety, which fell by 81 Bcm (-35%). In total, Europe’s gas imports fell by 18 Bcm (-5.3%) to 321 Bcm in 2022. This is roughly the same amount consumed in 2020, but the cost was more than ten times greater.

Get original energy commentary straight to your inbox. Sign up for free, or make a donation

Higher for longer, lower forever?

Europe’s gas bill is likely to remain elevated over the next 2.5 years even if demand remains depressed. The price ructions of 2022 may have subsided, but the forward curve remains structurally inflated well above the historical average.

Applying the same methodology as above, the value of all gas (imports + European production) likely to be consumed over the next 2.5 years can be estimated at roughly $600 billion even if demand remains flat.2

It could go higher if prices surge or demand springs back, but neither of these appear likely. Industrial gas consumption, which flexed down the most to balance the market when prices went haywire, shows no sign of immediate recovery. High costs erode the margins of energy-intensive industries, quelling appetite to reopen shuttered steel, fertiliser, chemicals, ceramics, and glass production facilities.

Thanks to the economising of heavy industry (and a slower pass-through of costs onto retail bills), households were spared the full burden of throttling back on gas consumption. Demand in this segment is particularly sticky because the political and human consequences of homes going cold are greater than a chemicals factory shifting to a three-day working week.

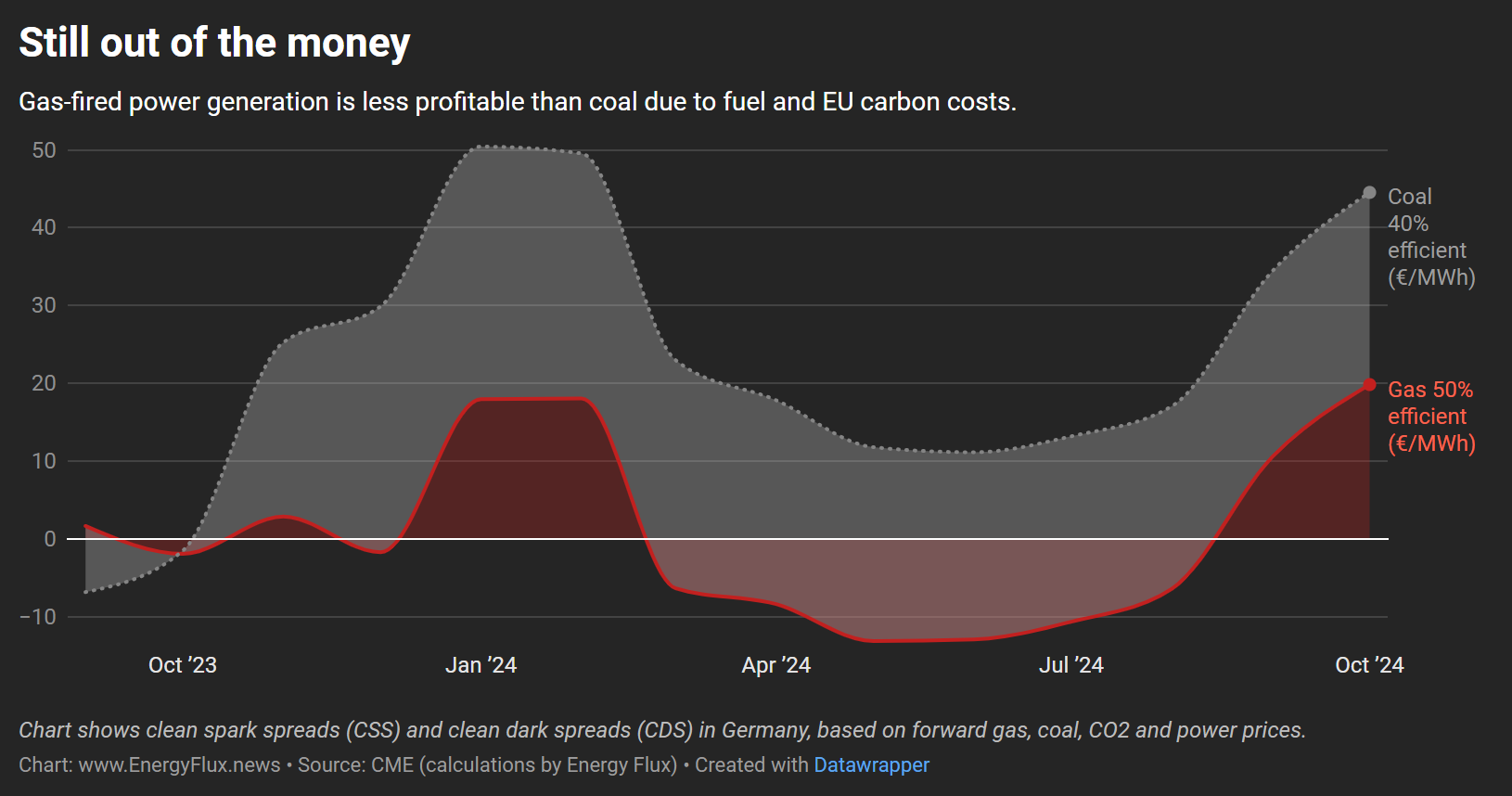

This puts a floor under gas demand, but historically elevated prices act as a ceiling. This holds true in electricity generation too, where expensive fuel and carbon costs are undermining the economics of gas-fired power (this has been the case since the start of this year). As the chart below shows, a 40% efficient coal plant has much more healthy profit margins than a 50% efficient combined cycle gas turbine.

Exporting misery (at consumers’ expense)

The trillion dollar figure is based on high-level data, so has a low confidence level and high margin of error. Nonetheless, it serves to illustrate the economic cost of hasty policy decisions taken in response to Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine. The rush to fill underground gas storage facilities at the height of the market was understandable considering the alternative – risk of physical shortages – but the costs were apparent at the time, and governments put consumers on the hook.

In Germany, state-backed gas market manager Trading Hub Europe (THE) was instructed to procure 50 TWh (5.12 Bcm) of gas on world markets to restock in time for an anticipated harsh winter that never arrived. The vast majority of that gas (37 TWh) remains in storage to this day, and the depreciation of the commodity means that THE is carrying a de-facto loss of at least €7 billion. Stored gas held by THE is almost unburnably expensive because prices would have to spike again to the crazy highs of 2022 for these volumes to come back into the money.

There are two scandals here: the first is that THE bought gas on the spot market unhedged because it was allowed to pass costs on to retail distributors via a special gas storage levy, which in turn will be recovered from consumers via their energy bills.

The second uncomfortable truth is that Europe’s $702 billion gas import bill amounts to an outsourcing of energy misery onto less wealthy nations. Crisis-stricken Pakistan is the poster child for wartime energy injustice: the country was left high and dry when traders rerouted cargoes to cash in on Europe’s LNG binge.

Thanks to European policies and liberalised markets, European consumers were unwittingly forced to bankroll this insanity. While they will be paying down the debt for years to come, Pakistan won’t receive a penny – or any favours from Europe if and when energy prices spike again.

All of this should focus minds on the urgent need to bend the curve on gas demand via energy efficiency measures, while ramping up renewables, transmission, and energy storage deployment rates. The post-Covid period has served as a painful reminder that energy markets are fickle. The costs of securing supplies at short notice on global markets in periods of turmoil can multiply as quickly as the benefits of doing so can evaporate.

Burning through a trillion dollars’ worth of gas is unsustainable for Europe in any circumstances. Even if global gas prices do ever fall back to genuine ‘pre-invasion’ levels, demand reduction is a no-regrets move: any policy costs will pay for themselves by taming Europe’s penchant for wild gas spending sprees when markets tighten.

© Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 12 July 2023

* Disclaimer: All opinions expressed here are entirely mine and not my employer’s *

Even in benign markets, wholesale prices swing strongly away from annual averages on a daily, weekly and seasonal basis. Benchmark TTF is a useful proxy for European wholesale gas but prices do vary significantly across the continent, particularly in semi-isolated markets such as the Iberian peninsula. A more accurate estimate of the value of volumetric consumption would require a more robust methodology and more granular data that correlates price movements with consumption over shorter time intervals. The extent and pace of wholesale price pass-through to households, businesses and industrial consumers would also need to be taken into consideration.

These forward-looking calculations are conservative because they are based on (currently benign) futures prices and an assumption that demand will remain flat at 449 Bcm per year in both 2024 and 2025. Both demand and prices are notoriously hard to forecast – particularly in periods of heightened volatility and shifting energy market dynamics. EU gas markets remain febrile and a harsh winter (or a supply shock) would reinflate Europe’s gas bill.

More from Energy Flux:

Chinese whispers, European jittersEurope, we are told, should fear China. A prevailing narrative in some energy circles is that post-Covid Chinese demand for liquefied natural gas will come roaring back and that Europe will face a much tougher task restocking gas for next winter than last time around.Is gas-fired power back in the money?Ultra-expensive gas rendered gas-fired power unprofitable for much of 2022 Recent falls in wholesale gas prices briefly reversed that situation Gas plant profitability could easily flip negative again, temporarily benefitting coal Economics still favour switching from coal to wind or solar PV plus battery storageEnergy markets are so damn fickleThree weeks is a long time in energy markets. Before the Christmas break, Europe was enduring a bitterly cold snap characterised by very low wind speeds and strong heating demand. The abysmal performance of France’s ageing nuclear fleet placed extra demand on dispatchable power generation. Christmas had come early for natural gas traders, or so it seemed.

Member discussion: Europe’s pyrrhic gas victory

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.